On May 10, 1940 Germany invaded France and with such military success that the French Government was forced to sign an armistice with Germany already on June 22nd, less than six weeks later.[1] The success of the Germans provided its Japanese ally with more leverage in the Asian theater of war and already on June 19th, 1940 Japan submitted to the Governor General of Indochina, Georges Catroux, with a demand to close all supply lines from Indochina to China.[2] An advantage that would logistically aid the Japanese fight against the Chinese.

While France was not keen to suffer infringements to its sovereignty, the semi-occupied country and a German aligned Vichy Government was in no position militarily or politically unwilling to defend the colony in Asia. The French therefore agreed to the demand a day later, resulting in the closure of the train line to Kunming by the end of June. This of course set in motion a rope-a-dope style action where the Japanese demanded more and more cooperation from the French in using Indochina as a war platform. These demands included naval basing rights, air bases, the right to transit troop movements, etc.[3]

Due to French recalcitrance, the Japanese Twenty Second Army finally crossed the Indochinese border to China on September 6th to provide gravity to the Japanese demands. This led to some skirmishes between the Japanese and French troops but also to protracted negotiations which ultimately led to an accord that met most of the Japanese objectives. This, set in motion a strange period in which one country (Japan) was essentially occupying Indochina while another country (France) was allowed to continue to administer it. This administration included the postal service but not the postal censure.

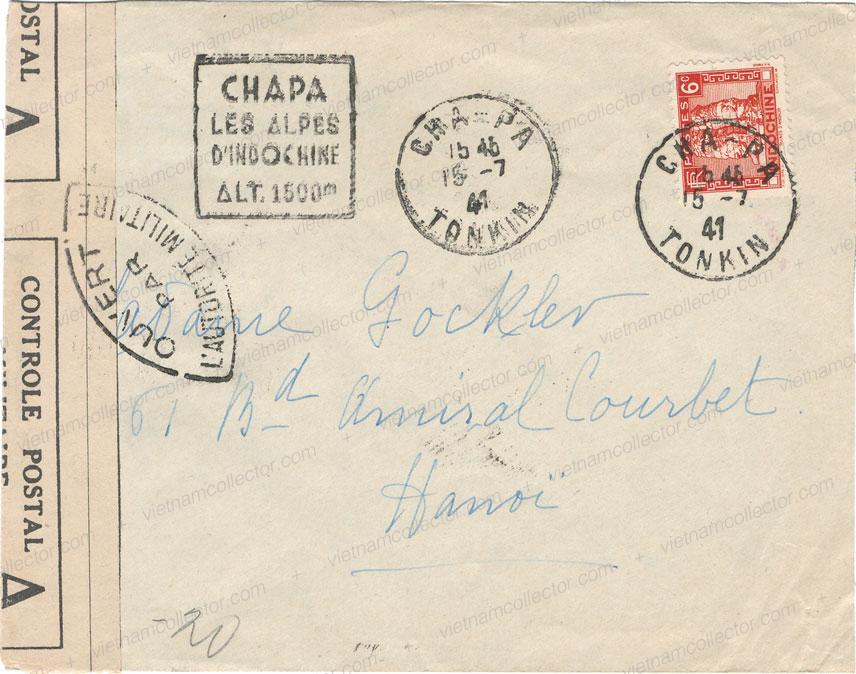

Single franking of the 6C stamp on a domestic letter sent during the Japanese Occupation of Indochina in July of 1941 from Cha-Pa (rare cancel) to Hanoi. The Japanese continued to use the same cachets and banderoles as the French did previously. So, while the censure marks and tape are French they were in fact administered by the Japanese. Hanoi arrival cancels on the reverse. Boxed cachet “Chapa the Alps of Indochina, Alt. 1,500m” on front.

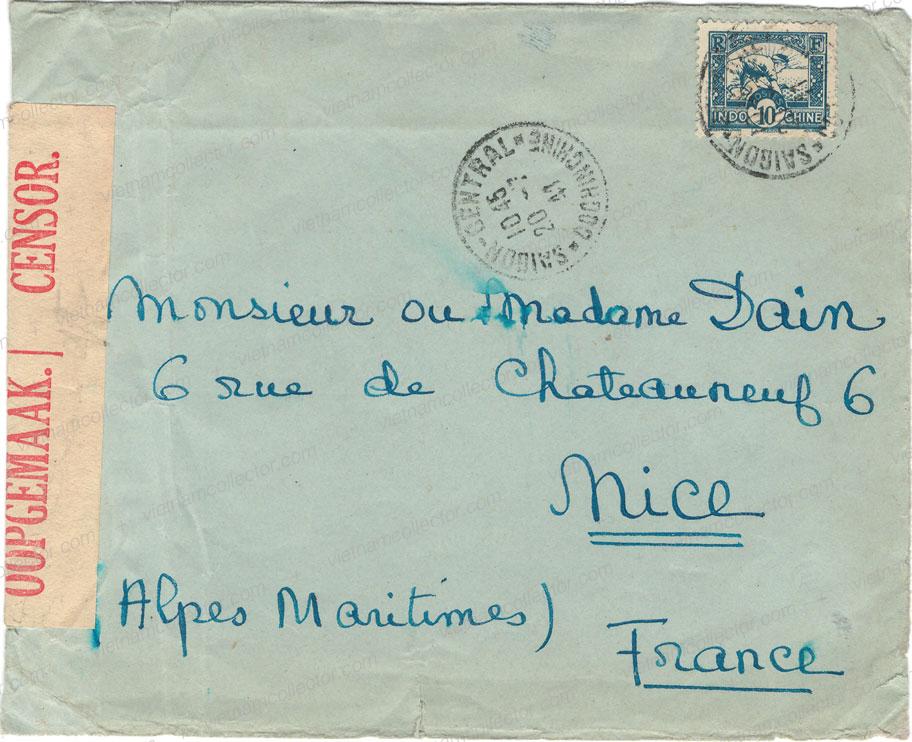

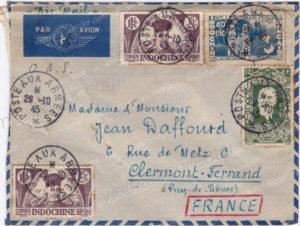

Single franking of the 10C value (blue) on an international printed matter mailing sent from Saigon Central to France in July of 1941. Since the letter was addressed to the part of the country that was affiliated with the German occupiers (Vichy) it was not censored by the Japanese that occupied Indochina at the time. However, the letter got intercepted in South Africa and was censored by South Africa that was aligned with the British Empire as indicated by the red censor banderole used to re-seal the letter.

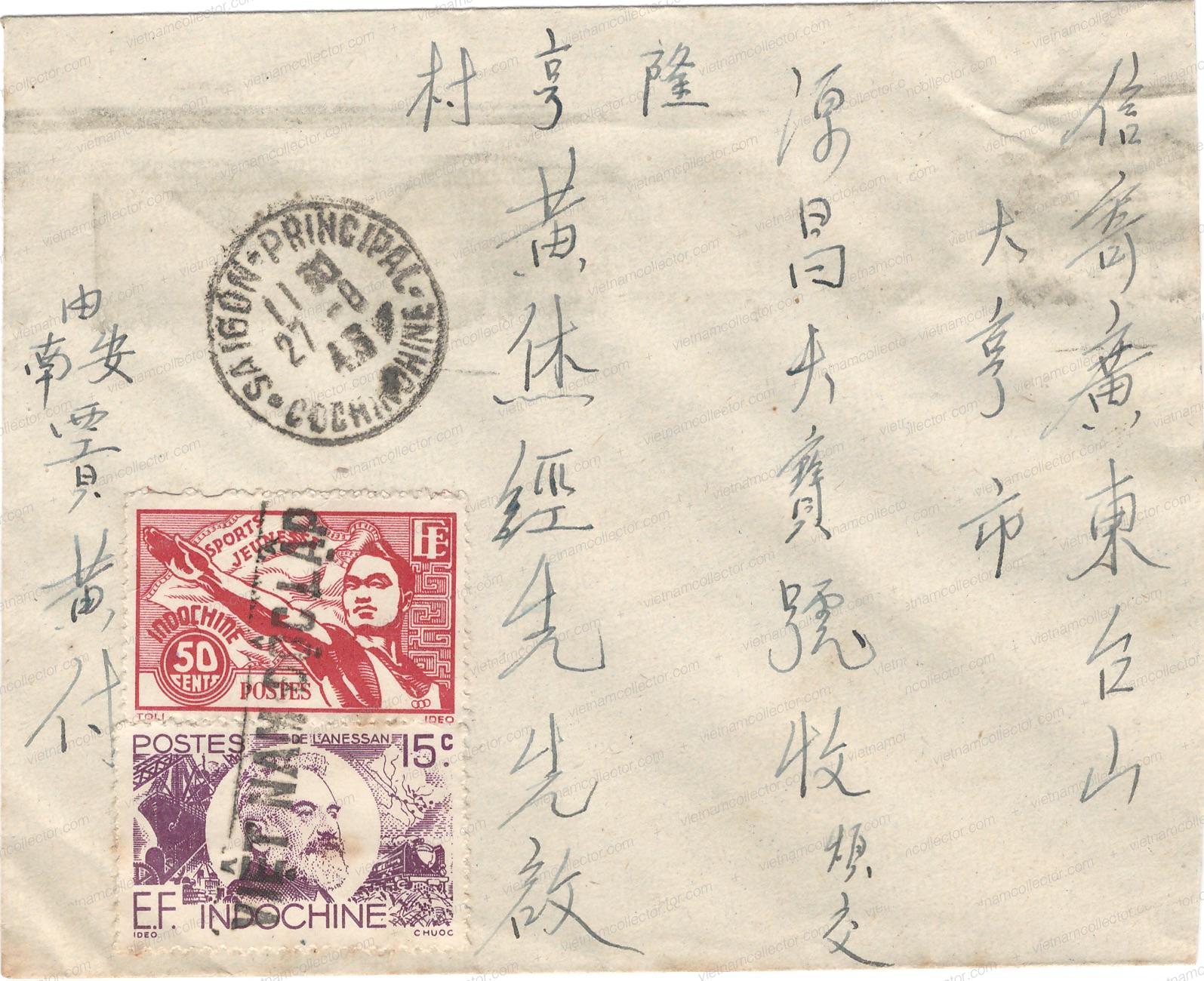

Very rare mixed franking of the 15C (blue) and 50C stamps paying an overall postage of 65C on a registered international letter (40 grams) sent from Saigon to Japan. This was during the Japanese Occupation of Indochina. The bank was privileged as it was exempt from the standard mail censure even during that time as indicated by the red hand stamp “Sce de la Banque Privilege del Indochine”.

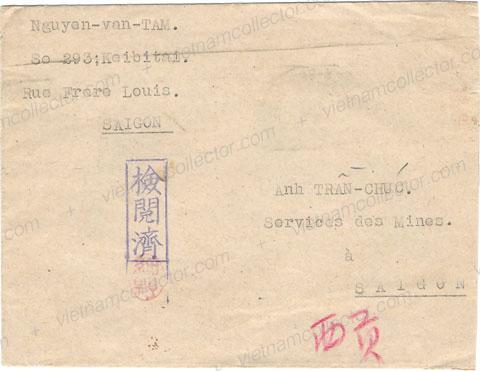

The Japanese, focused on defeating the Chinese, were initially not interested, to saddle themselves with additional responsibilities consuming money and man power that a full occupation would have demanded. They instead showed a relatively light touch that also left the existing French postal system pretty much alone. Very few Japanese censor marks appear at the time and it was mostly official and company mail that was occasionally censored. The very rare letter below, which is ex Desrousseaux, shows a letter from a Japanese Fishing Company in Haiphong to the Director of Mining Services in Hanoi (a post occupied by J. Desrousseaux). The violet Japanese censor stamp along with the red seal of the censoring officer is prominently displayed on front. Japanese Military Mail was, of course, not transmitted using the French postal system but the Japanese Military Mail system.

Below is another very rare letter (ex Desrouseaux) that was sent by an individual in 1945 in Saigon to a person working in the Mining Company Office in Saigon. It shows a very weak circular date canceler on front and two weak transit cancels on the reverse. Japanese censor marks on front.

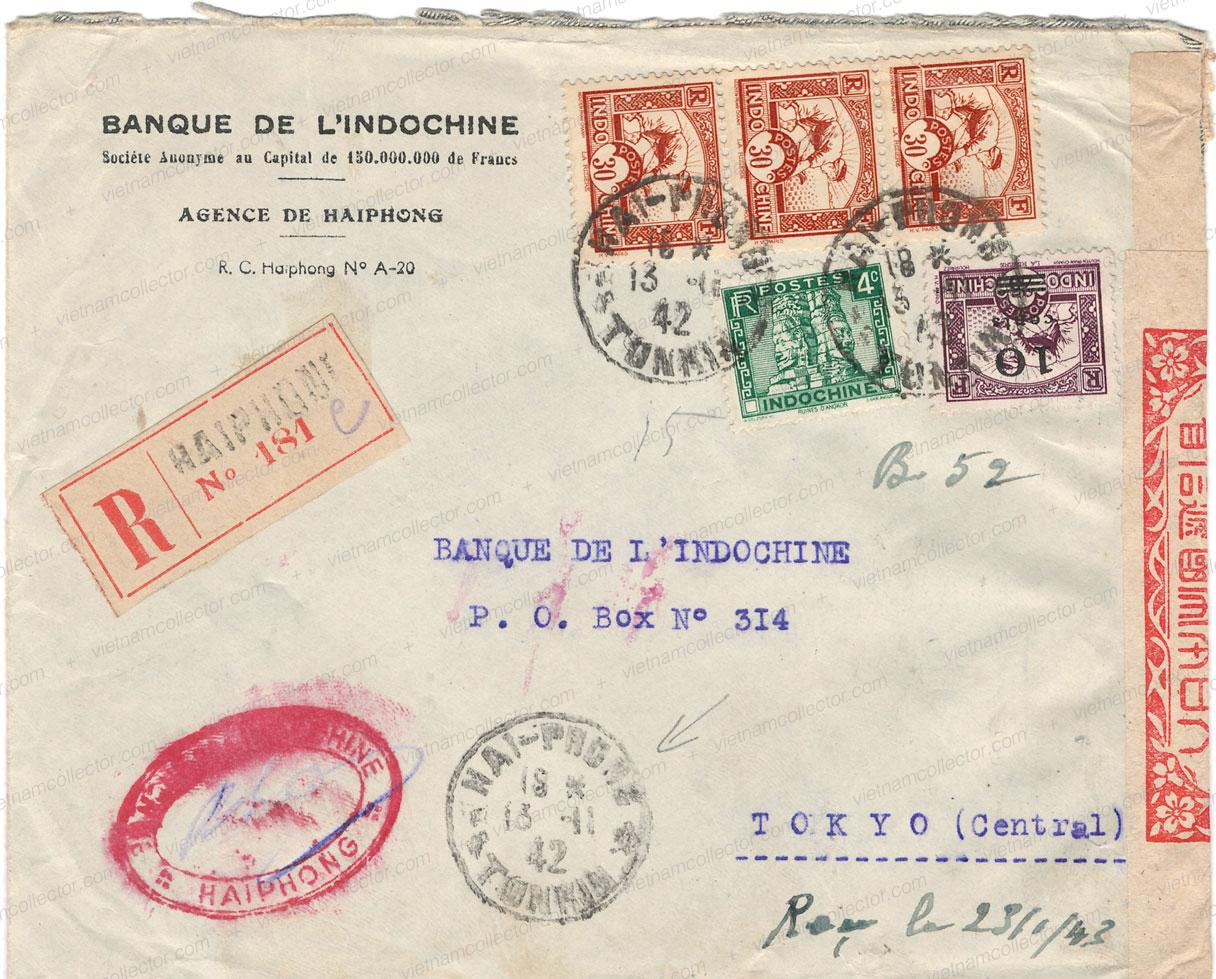

Mixed franking of Domestic Motives II stamps together the overprinted 25C stamp paying an overall postage of 1.04P on a very rare international registered letter sent during the Japanese Occupation from Hai Phong to Japan in November 1942. The letter was censured by the Japanese as evidenced by the Japanese censor tape along with a circular Japanese center cancel on the reverse.

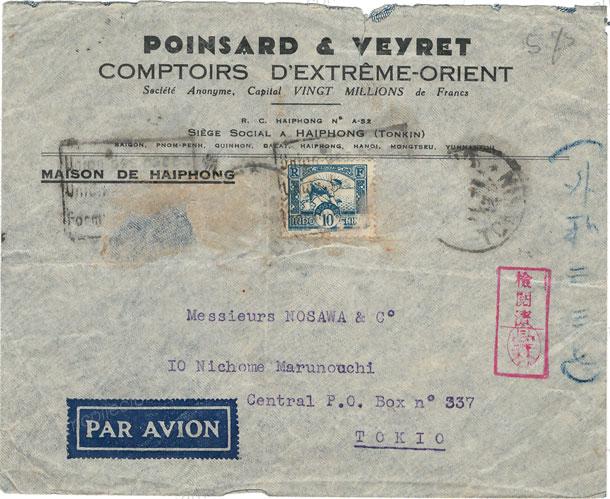

Rare international air mail letter during the Japanese occupation that was sent from Hai Phong to Tokyo in July of 1942. Some stamps appear to have fallen off. Red rectangular Japanese center cachet and blue manuscript censure marks on front. Hanoi and Saigon transit cancels on the reverse. Tokyo Central 5th August in Showa 17 (=1942) arrival cancel on the reverse.

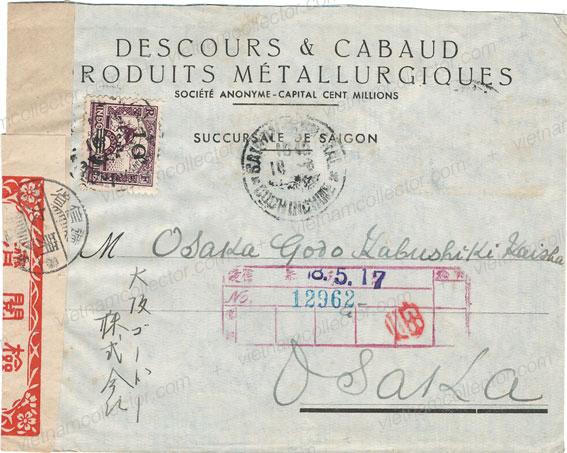

Another rare international letter under Japanese occupation sent by a metallurgic company in Saigon to Osaka in Japan. Red/orange censure cachet/marks on front. Opened and sealed with Japanese censure tape and circular censure cancel.

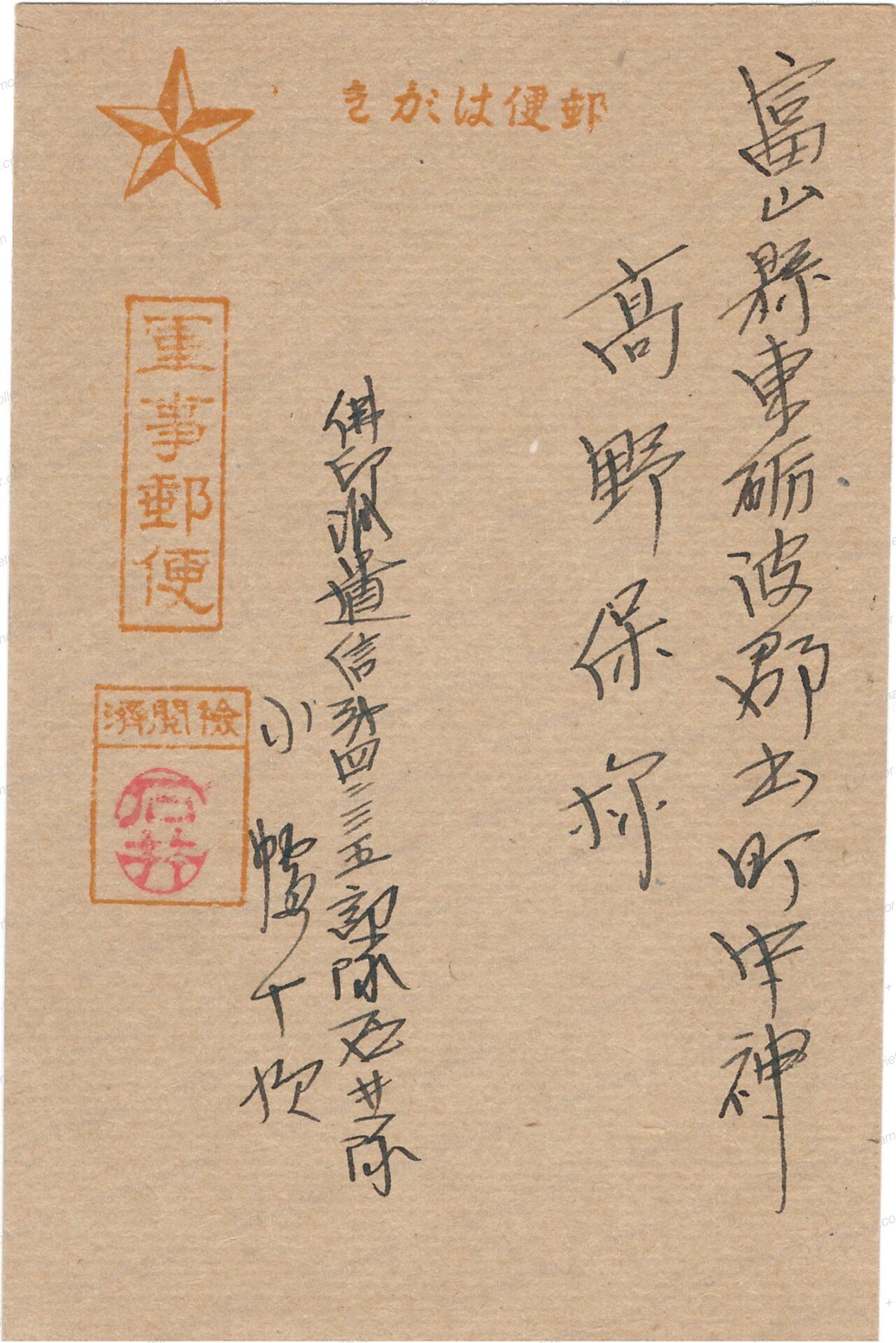

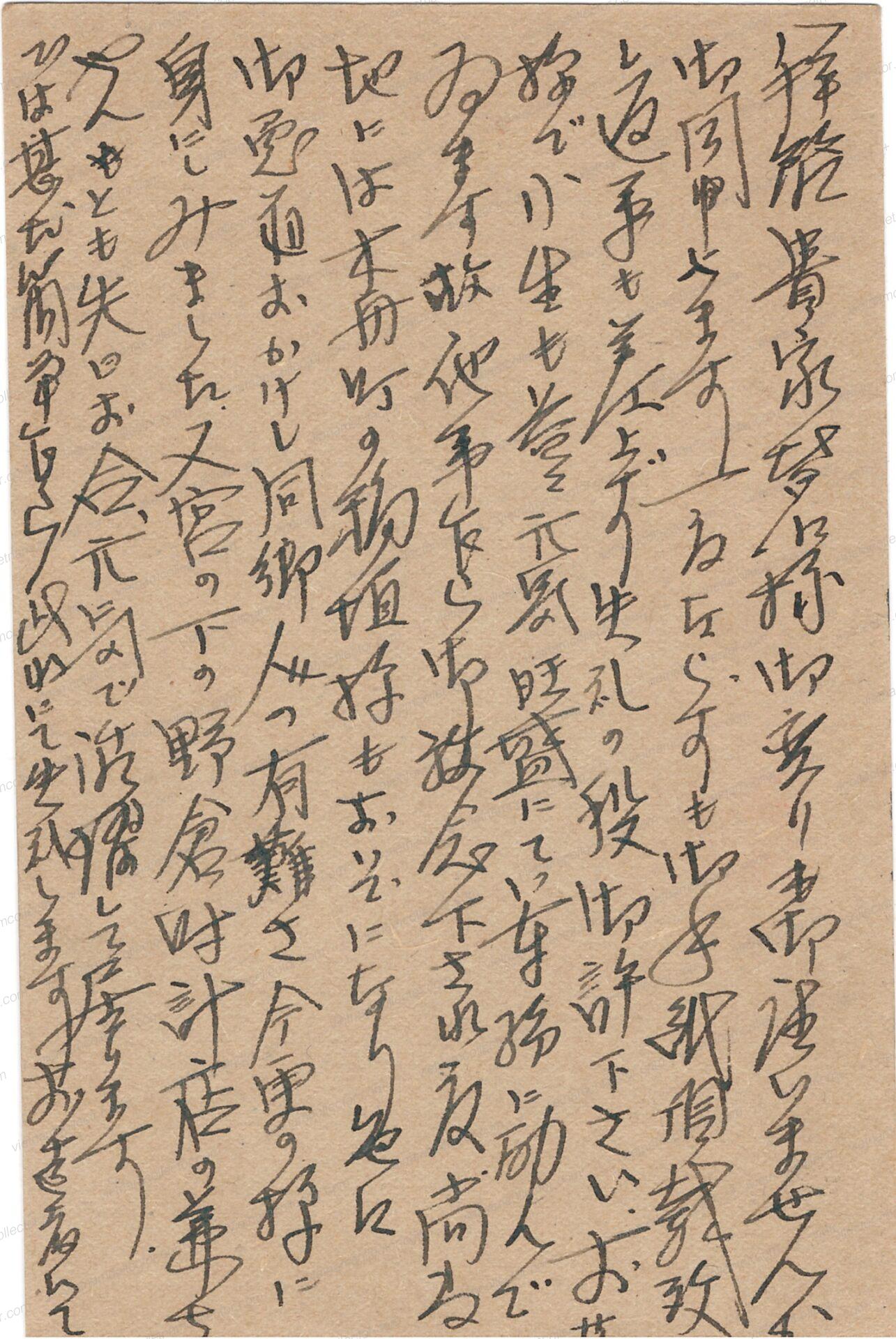

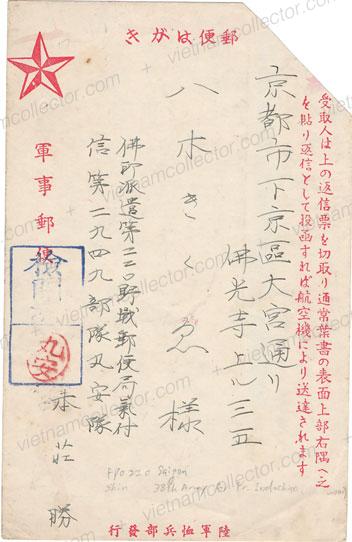

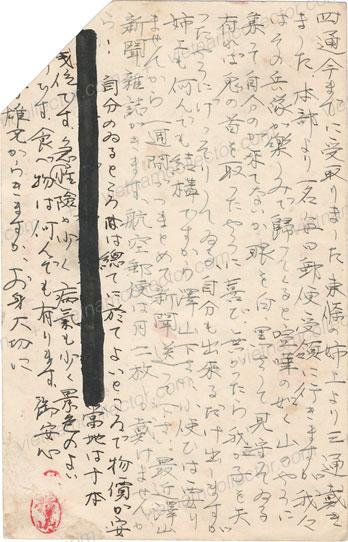

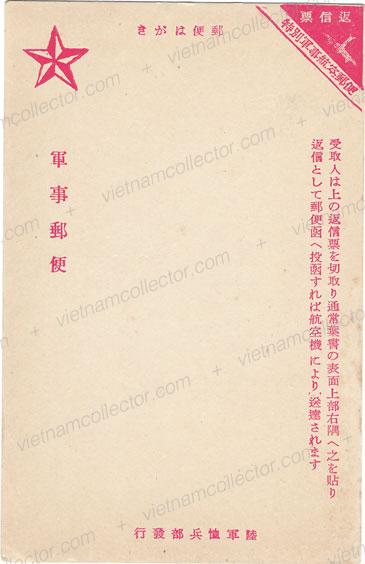

Below is a military air post card from Masaru Honjo of the Maruyasu Party, 38th Army, Shin 2949 Unit, Field Post Office 220 of the French Indochina Dispatch stationed in Hanoi to Kyoto City. Again, you can see the Japanese censor mark in front and an additional censor mark on the back. Among a general description of usual soldier’s sentiment, he writes:

I don’t need money but send me newspapers every week as we can only receive two air mails per week.”

The cut corner, by the way is no deficiency. It featured the imprinted postage stamp that was cut off as a sign that the card had been used. Here is a similar card that is unused and hence shows the intact free frank imprint.

A very similar card in ochre color exists. Here is a sample sent from Indochina to Toyama Prefecture in Japan. Red censor marking in the lower box on front. The contents of the card is limited to personal greetings and very generic information owed to the censorship.

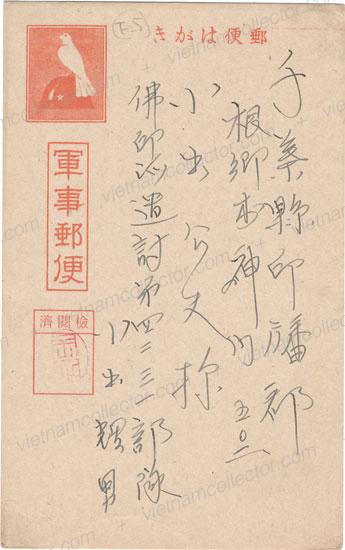

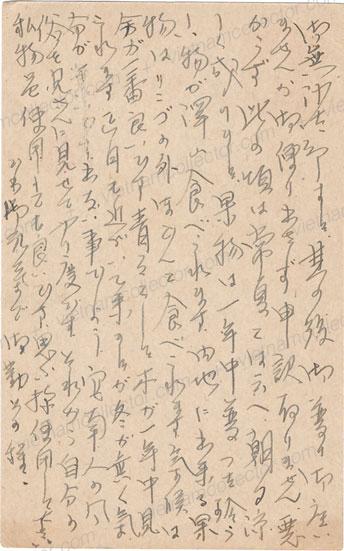

Here is another type of Japanese military postal stationary that was sent from Aman to Japan. Sent by a Teruo Koide, Tou 4231 Unit, Fr. Indochina Dispatch (Tou meant Inf. 21. Division 4231 which was the Headquarter of the 21st Infantry Division which served in Northern Indochina). Sent to a Kimio KOide, 502 Negohongami-Town, Inba-Gun, Chiba Prefecture. Censored by Okada. The soldier writes to his brother about fruits and habits of the Anamese.

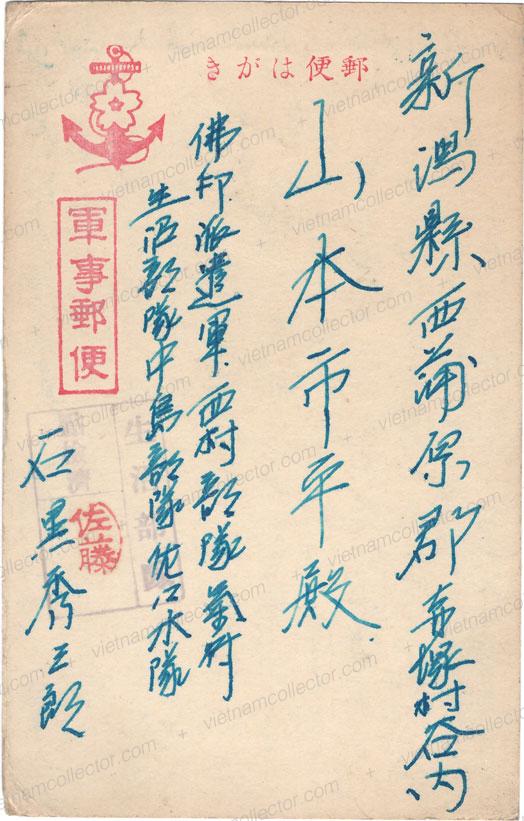

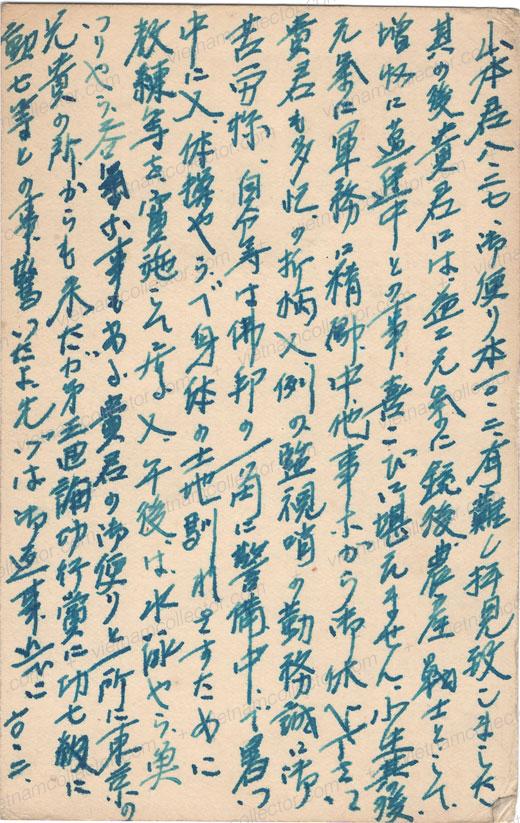

Here is the Navy version of the Japanese free frank post card. It was mailed by Hidegoro Ishiguro of the Indochina Expeditionary Army, Nishimura Unit “KIFU” Ikunuma Unit/Nakashima Unit/Sasaki Corps to a Mr. Ichihei Yamamoto, Nigata Prefcuture Nishikanbara-Gun Akazuka-Mura Taniuchi. The vertical red bar means “Military Post”. The violet cachet is the censor mark and the red hand stamp inside the censor mark the censor identification. The soldier writes that ” I was sent to Indochina in order to get used to the country. In the mornings I learn different things and in the afternoon I go to the beach or enjoy fishing”.

Poorly documented

Philatelically, the Japanese occupation of Indochina is poorly documented. In the SICP Journal Nr. 12 from June 1973 Desrousseaux, who, having lived there at the time, was the ultimate expert on the subject, writes

Mail was very scarce during the Japanese period owing to the U.S. Bombing which destroyed all boats and railway bridges.”

He adds

We have never (seen) a single letter from or to foreign countries during this period even under Japanese occupation. Covers or cards of that period are very rare, especially with characteristics markings other than the date.

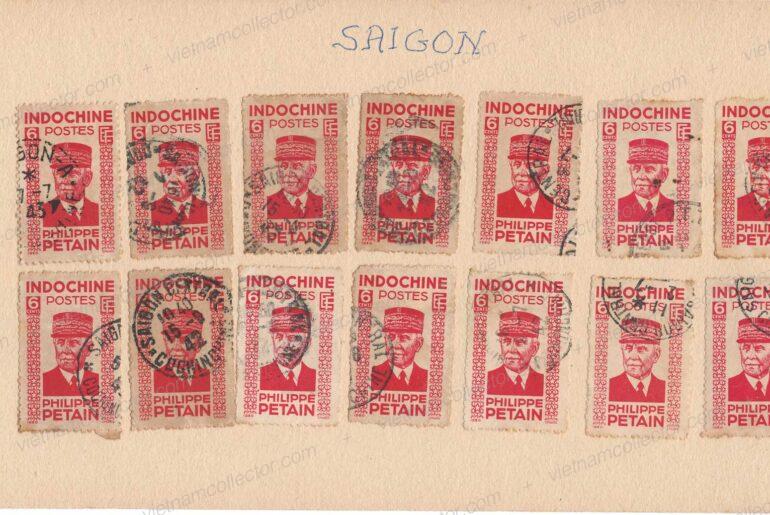

So, of course, with that kind of challenge the authors philatelic “hunting instincts” were on to systematically scan his collection and cover offerings just for such material. The result was a few covers that seemed to fit the bill of additional markings and foreign mail. Below is a cover front featuring a pair of 40 cent blue-green Petain stamps from a registered letter mailed on February 19, 1943 from Saigon to Thailand. Please note the French circular censorship mark at the bottom left, that the Japanese continued to use. According to Desrousseaux the Japanese often unglued the envelopes by steam and so did not always use the old French banderoles.[4]

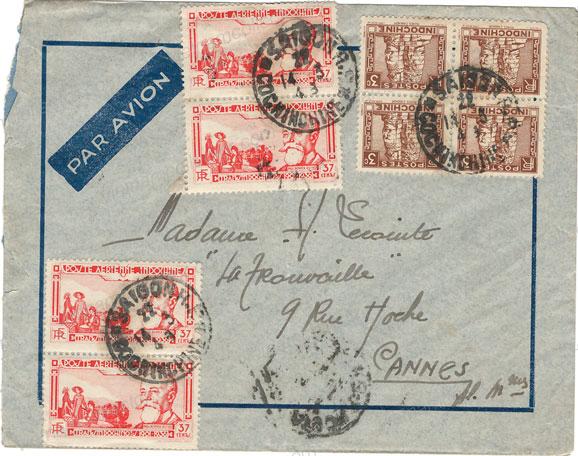

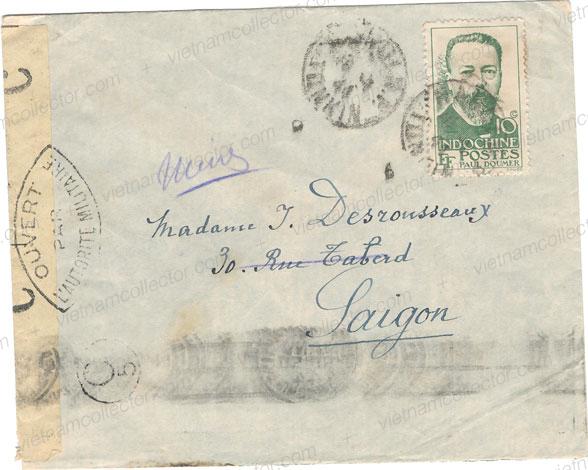

Below is a cover sent on March 14, 1943 from Saigon to Cannes. Since that was situated in a part of France controlled by the German aligned Vichy Government the cover was not censored (Germany was a Japanese ally). The next letter shows a domestic cover sent from Hanoi to Saigon to, what the editor presumes was Desrousseaux’s wife. The cancel is a bit smeared but the date looks like April 16, 1944. The 10C domestic tariff came in force on December 1st, 1943 and lasted until the end of December 1944. Again, the cover was censored by the Japanese using the old French military censor marks and in this case the banderole “Controle Postal Militaire”. Why this civilian cover was picked out to be censored is not known but it may have to do with the fact that J.Desrousseaux was employed as a high-level manager in the mining industry, and that the Japanese wanted to keep tabs on key industries and its personnel.

Below is a cover sent on March 14, 1943 from Saigon to Cannes. Since that was situated in a part of France controlled by the German aligned Vichy Government the cover was not censored (Germany was a Japanese ally). The next letter shows a domestic cover sent from Hanoi to Saigon to, what the editor presumes was Desrousseaux’s wife. The cancel is a bit smeared but the date looks like April 16, 1944. The 10C domestic tariff came in force on December 1st, 1943 and lasted until the end of December 1944. Again, the cover was censored by the Japanese using the old French military censor marks and in this case the banderole “Controle Postal Militaire”. Why this civilian cover was picked out to be censored is not known but it may have to do with the fact that J.Desrousseaux was employed as a high-level manager in the mining industry, and that the Japanese wanted to keep tabs on key industries and its personnel.

By September of 1944 the tide of war had changed and Germany was driven out of France by the Allied Forces. After the liberation of Paris, the Allies created a Provisional Government of the French Republic under de Gaulle which disbanded the traitorous Vichy Government in the South. [5]

By September of 1944 the tide of war had changed and Germany was driven out of France by the Allied Forces. After the liberation of Paris, the Allies created a Provisional Government of the French Republic under de Gaulle which disbanded the traitorous Vichy Government in the South. [5]

The German retreat quickly put pressure on the Japanese. By March 1945 it was clear to most, that Germany would lose the war. This meant that European troops and resources could eventually be transferred to Asia to fight the Japanese. Being afraid of an Allied Invasion of Indochina, the Japanese therefore decided that leaving the French, who now were no longer beholden to Germany, in charge of administering the State would be a bad idea. So, on March 9th, 1945 the Japanese staged a coup they called “Operation MEIGO” or “Operation Bright Moon” and imprisoned most French troops and some high level French civilians in concentration camps taking over all Government functions, including the mail. Some French troops were able to flee across the border to China.[6]

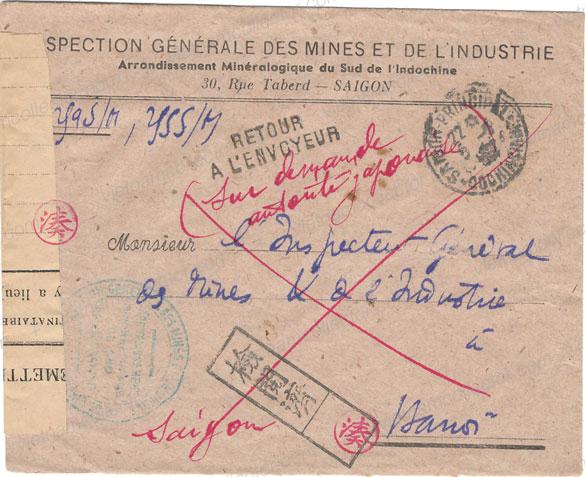

Mail from this period which lasted less than six months, when the Japanese finally surrendered, is especially scarce. This letter above depicts a letter similar to the one featured by J. Desrousseaux in SICP Journal Nr. 13. Among various Japanese censor markings and a censor band that was fashioned out of a journal, it shows a stamp “Retour a L’Envoyeur” and a red manuscript “on request of Japanese authorities”. On this he writes

Mail from this period which lasted less than six months, when the Japanese finally surrendered, is especially scarce. This letter above depicts a letter similar to the one featured by J. Desrousseaux in SICP Journal Nr. 13. Among various Japanese censor markings and a censor band that was fashioned out of a journal, it shows a stamp “Retour a L’Envoyeur” and a red manuscript “on request of Japanese authorities”. On this he writes

After March 10 Indochina Post Offices were only allowed to send and deliver a very small number of letters bearing a military marking or a manuscript warrant from Japanese authorities. The general mail was seized by the Japanese in the post offices and mail vans were usually destroyed. After censoring it they sent back to the addressor only the official mail. Some private letters sent before March 9th reached their addressees at the end of April.”

By March 11th, 1945 the Japanese, who themselves were an occupying force, encouraged different regions in Indochina to declare independence from their former French colonial masters. This was a purely defensive action by the Japanese to get the Viet Minh, who had battled the Japanese occupation force from the underground for a while, onto their side or at least off their back. In this context Yokoyama Seiko, Minister of Economic Affairs in Indochina, permitted Emperor Bao Dai to formally declare Vietnams independence and establish the Empire of Vietnam.

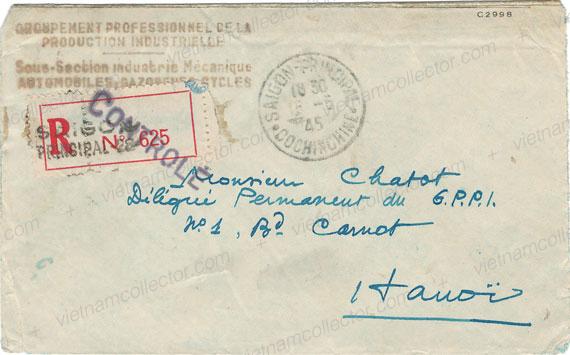

Below is a registered commercial letter from Saigon to Hanoi mailed on May 15th, 1945. The 45C postage paid the 15C standard domestic letter rate plus 30C for registration. The letter carries a linear Japanese censor stamp on the registered label “Controle”, which originally came from the French telegraph control office.[7]While nominally Japan had declared independence it was clear that the Japanese occupying force was still in charge politically and militarily in Indochina.

The Hanoi arrival stamp on the back is dated August 8th, 1945 indicating that it took almost 3 months for the letter to be delivered by foot messengers or low tech means of transportation such as pirogues or ox carts. Parallel to the Japanese take-over, Viet Minh groups were quickly set up in districts and provinces throughout Northern Vietnam and among the ethnic Viet in Laos to organize resistance movements against the Japanese. [8]

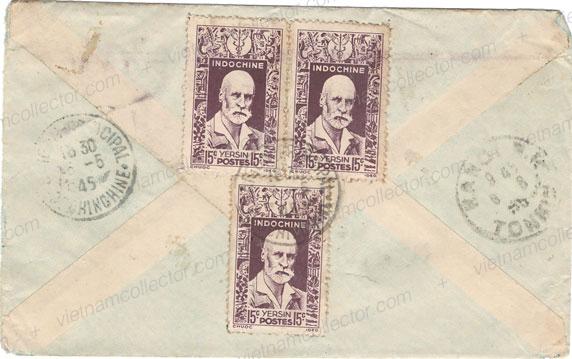

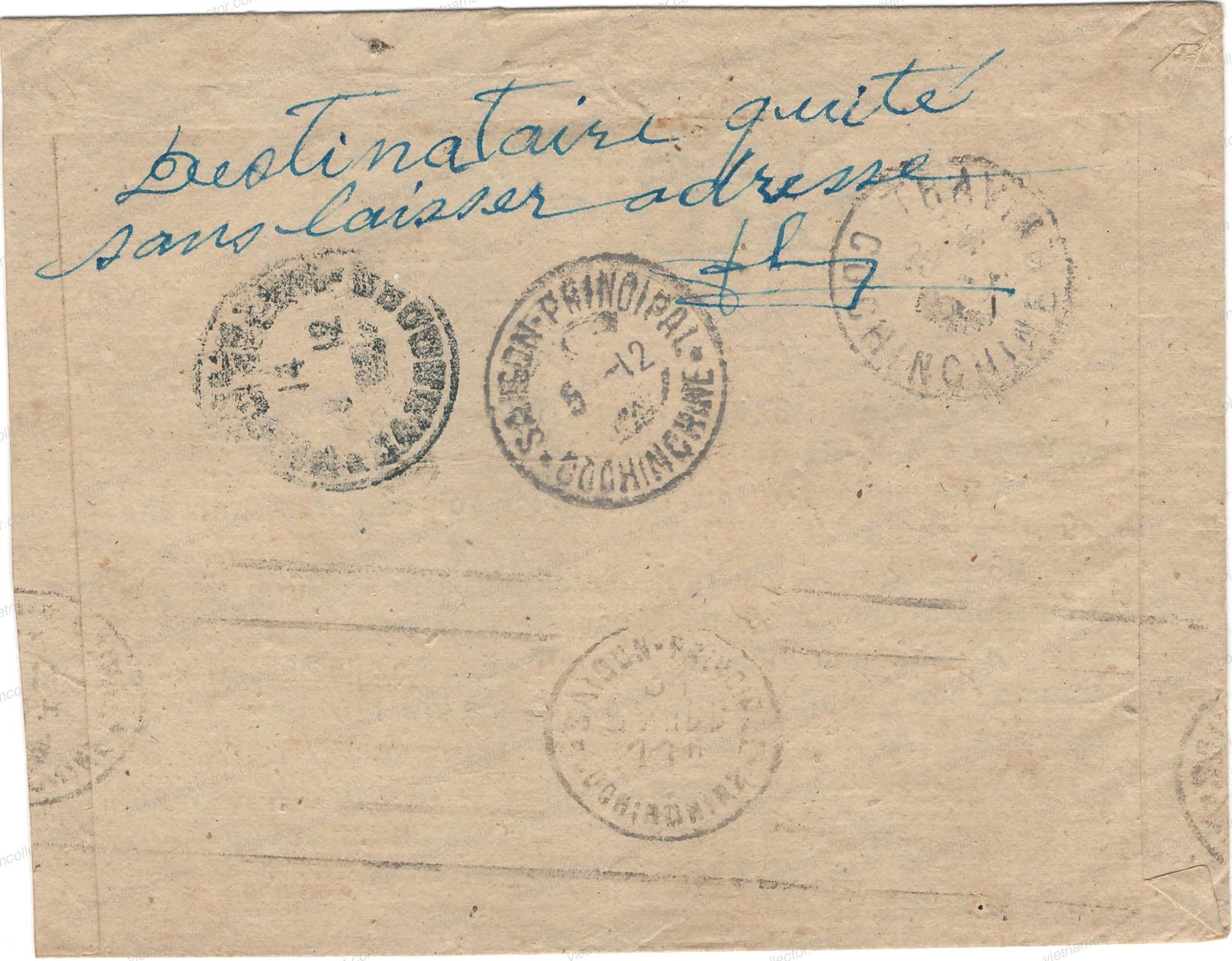

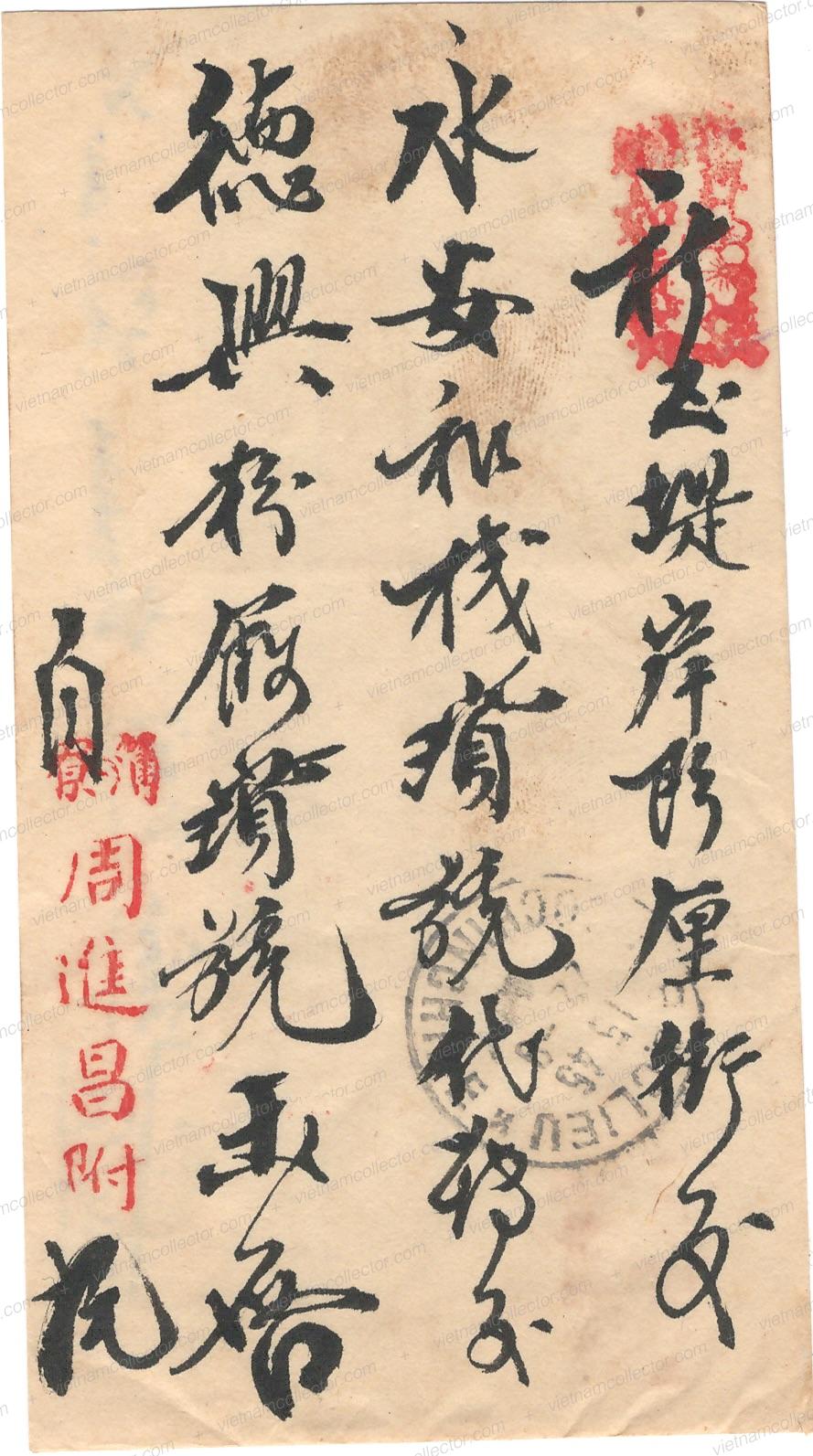

Already by June 1945 Vietnamese propaganda cachets supporting Vietnamese identity or proclaiming the independence of Vietnam started to pop up alongside the postal markings that were still in French. Here is a domestic letter correctly franked with a 15C Alexandre de Rhodes stamp that was sent on July 26th, 1945 from Tieu Can in Cochinchine to Phnom Penh in Cambodia. Apart from the city and State the address was written in Thai which apparently could not be read by postal workers. The address was hence crossed out with blue ink and a French cachet “Parti Sans Liaison d’Adresse” or Party without address was applied on front. Also a Vietnamese propaganda cachet stating “Vietnamese only write in Vietnamese” and French cachet stating “Return to Sender” was struck. The letter went onto an odyssey through Tra Vinh on July 26th, 1945, Saigon on December 5th, 1945 and finally Pnom Penh on December 14th, 1945 as indicated by the transfer cancels on the back.. A manuscript handwriting “Recipient without leaving address” was noted on the reverse. How the letter made it back to the sender is unknown.

After the United States dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6th and 9th of 1945, Japan requested an armistice on August 15th. With all French troops being imprisoned or having fled a power vacuum was created that was immediately used by Vietnamese Nationalists and the Viet Minh to take charge by seizing control of the major cities and all key administration centers in the country.[9]

The Japanese, realizing that all was lost, offered no resistance and left the field pretty much to the Viet Minh and Nationalists to make it more difficult for the French to return to power. By August 19th, the Viet Minh had seized Hanoi and taken over the mail in all over the country. Very quickly, Nationalistic Vietnamese, French and Chinese slogans were now used to undermine the return of the French.

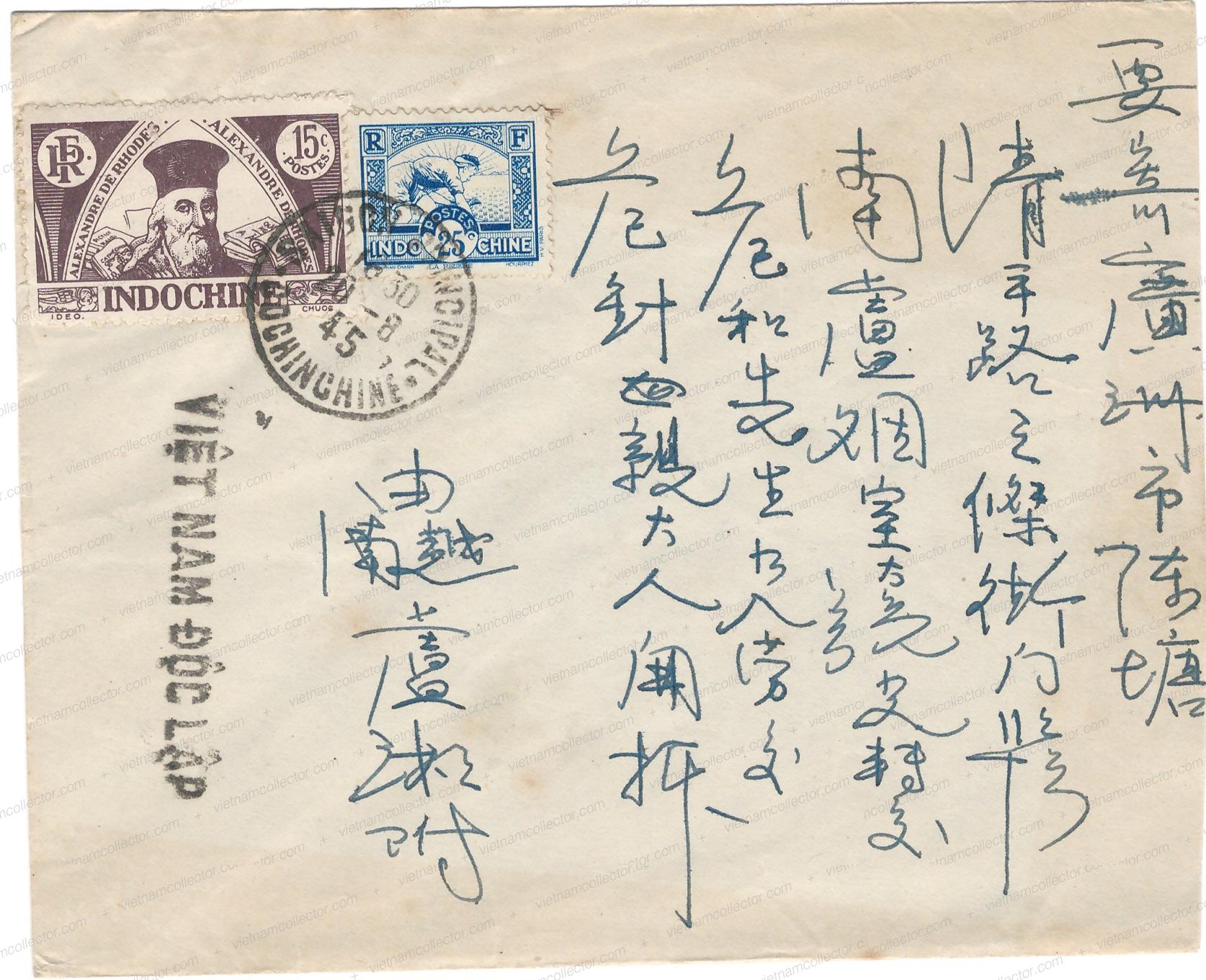

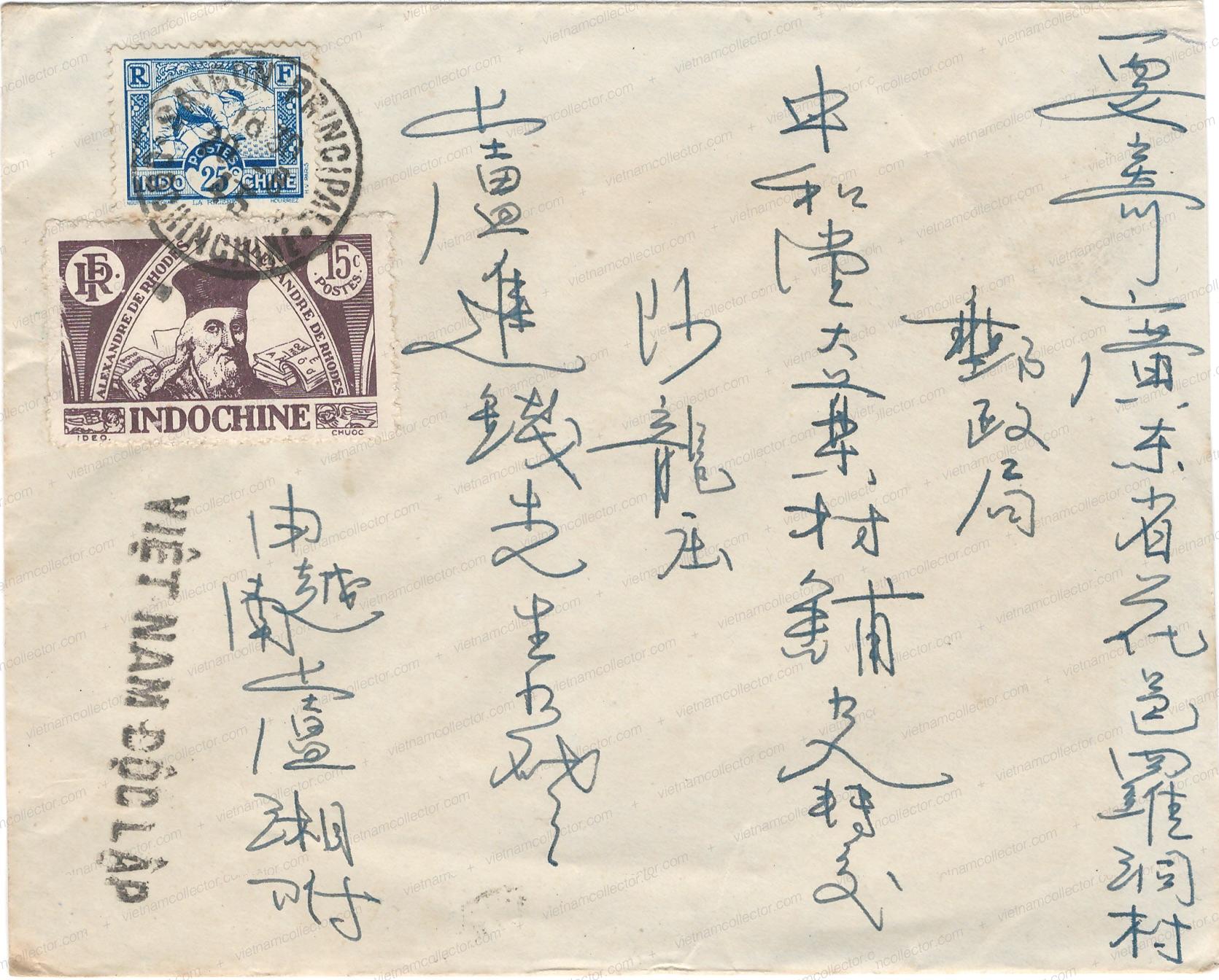

Here are interesting international letters that were mailed on August 20th, 1945 from Saigon to Malaysia. They were properly franked with 40C. While it was clear that after Hiroshima and Nagasaki the Japanese were not going to win the war they did not formally surrender until September 2nd, 1945. Japan also occupied Malaysia and this probably accounts for the fact that the letters were not censored at all. The increasing Viet Minh influence in the postal system is symbolized by the very rare propaganda cachet “Viet Nam Doc Lap” which means “Vietnam Independence” and that was struck on front. This cachet was only used on August 2nd of 1945 and then again from August 15th until the end of August, both in Saigon. It is exceedingly rare, especially on an international letter as there was little postal traffic after the Japanese took full control of Indochina in March of 1945.

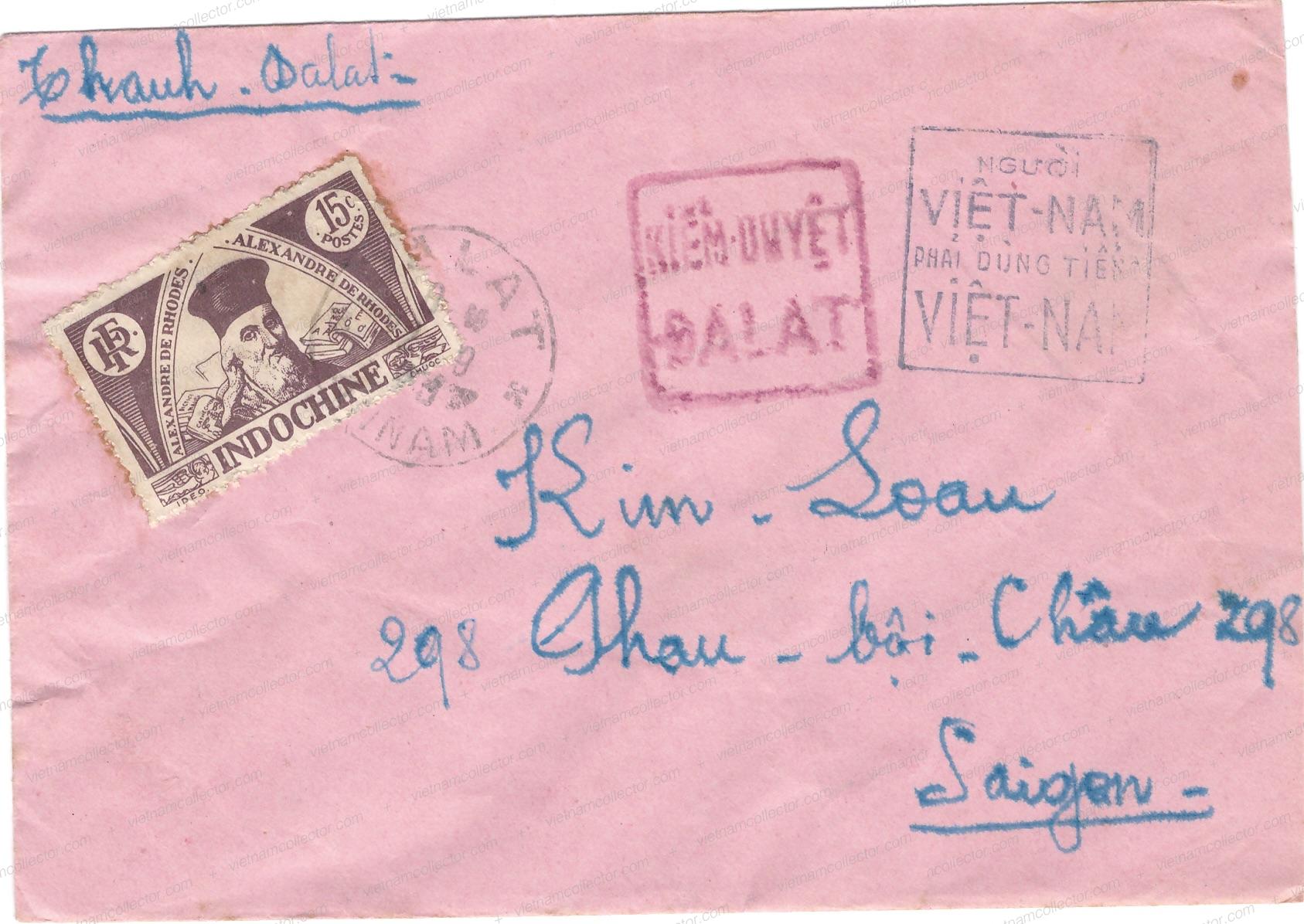

By July of 1945 we can also witness that the Viet Minh had taken control of the Indochinese postal system as they started to censure mail in addition to the propaganda cachets in Vietnamese. Here is a local letter properly franked with 15C that was sent in September off 1945 from Dalat to Saigon. It carries the propaganda cachet of “Vietnamese only write in Vietnamese” along the red Viet Minh censor cachet of “Kiem Duyet Dalat”.

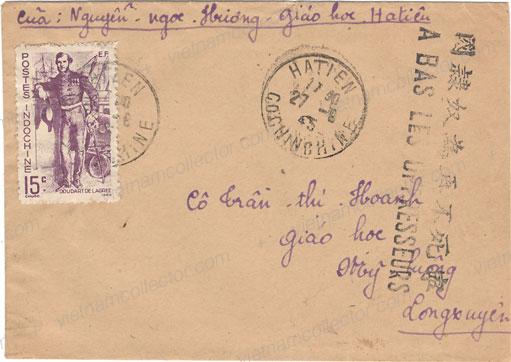

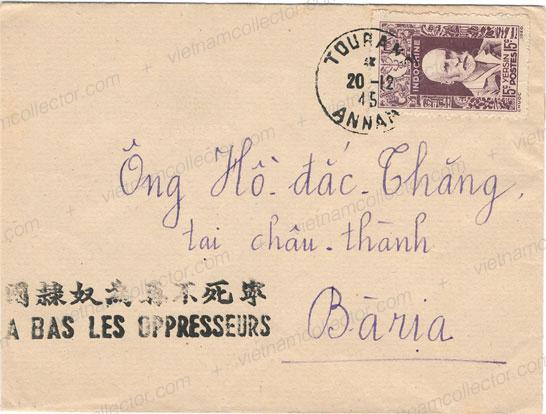

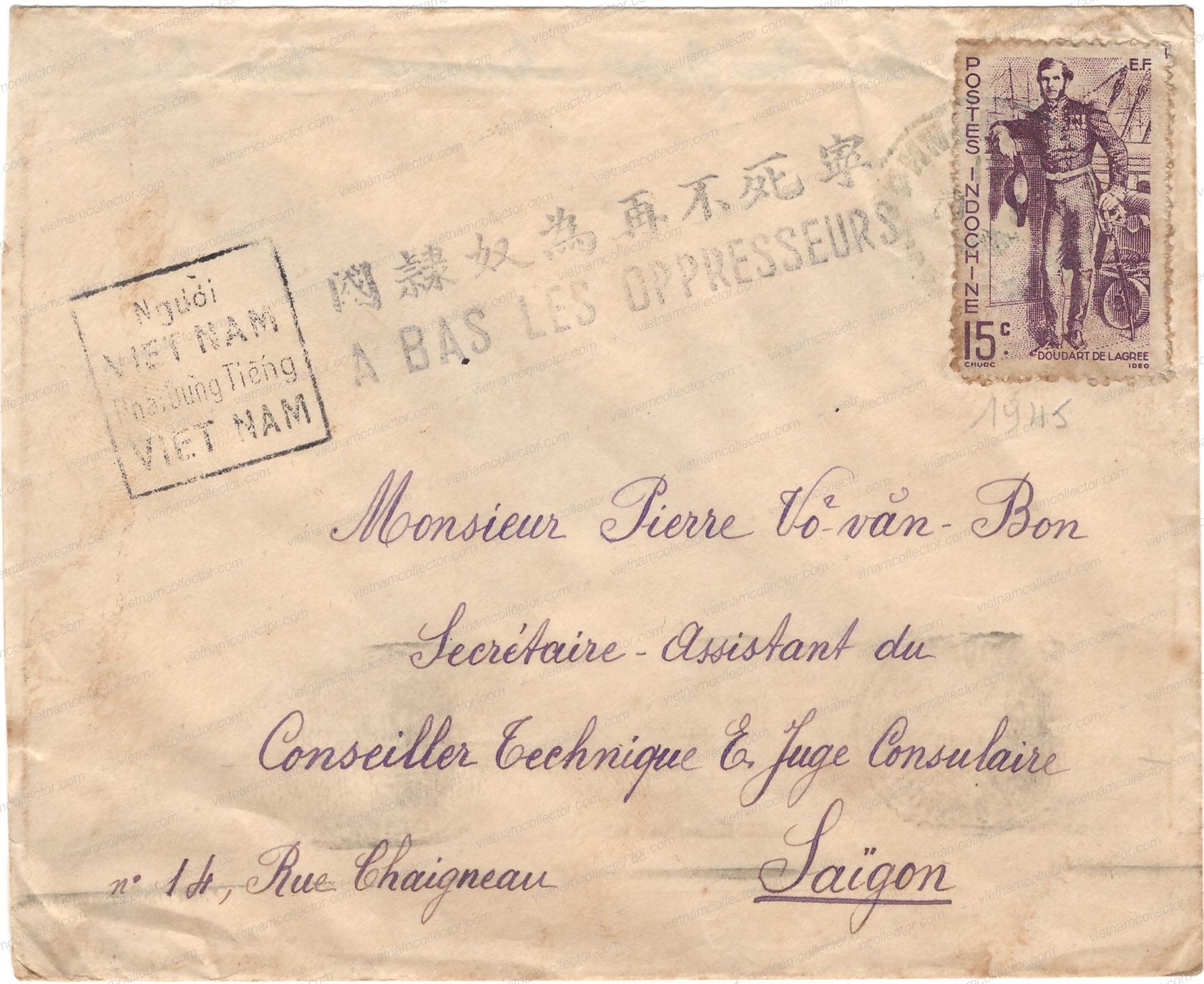

The two letters below show letters mailed on August 27th, 1945 (5 days before the formal surrender of the Japanese on September 2nd) from Hatien in the North to Long Nguyen north of Saigon and on December 20th, 1945 from Tourane to Baria an easterly province of Cochinchina. Both carry a black two-line hand stamp in Chinese and French that states “Down with the oppressors” in French and “Prefer Death to being a slave country” in Chinese. It appears that the cachet was in use for about 3-4 months for all mail that was routed through Saigon.

Here is another example of the “Down with the oppressors” in French and “Prefer Death to being a slave country” in Chinese propaganda cachet along with the “Vietnamese only write in Vietnamese” Daguin on a letter that was sent from Cambodia to Saigon probably in late August or early September of 1945 (cancel illegible).

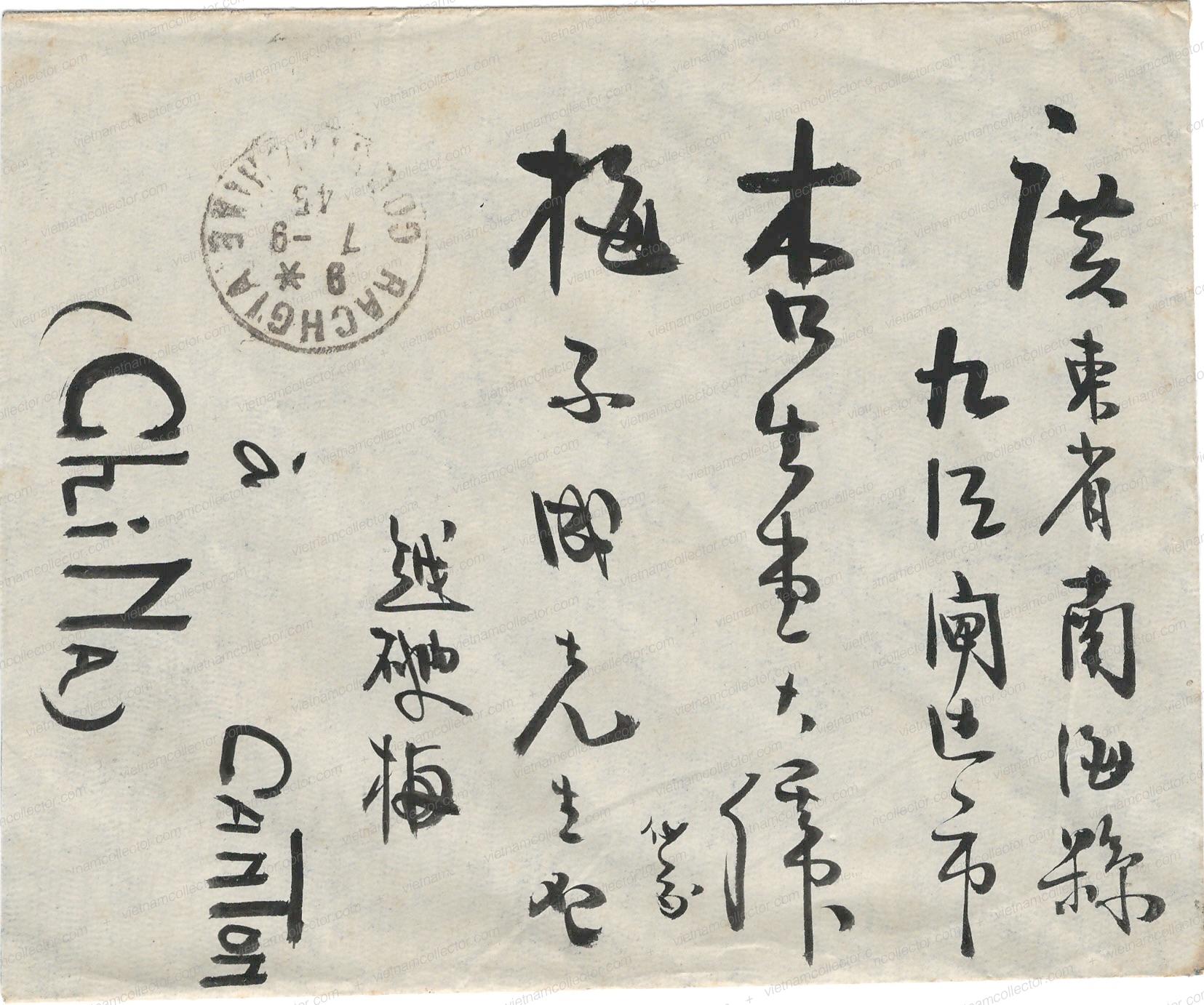

Here is a rare international letter that was properly franked with 40C and was mailed from Rach Gia to Canton in China. Until the end of the war Canton was occupied by the Japanese Army. While the Japanese surrender had taken place on September 2nd, 1945 this letter dated September 7th was still distributed without any censorship. It was routed through Saigon on September 11th as indicated by the machine cancel on the reverse were it also received the Viet Minh propaganda cachet of “Down with the oppressors” in French and “Prefer Death to being a slave country” in Chinese.

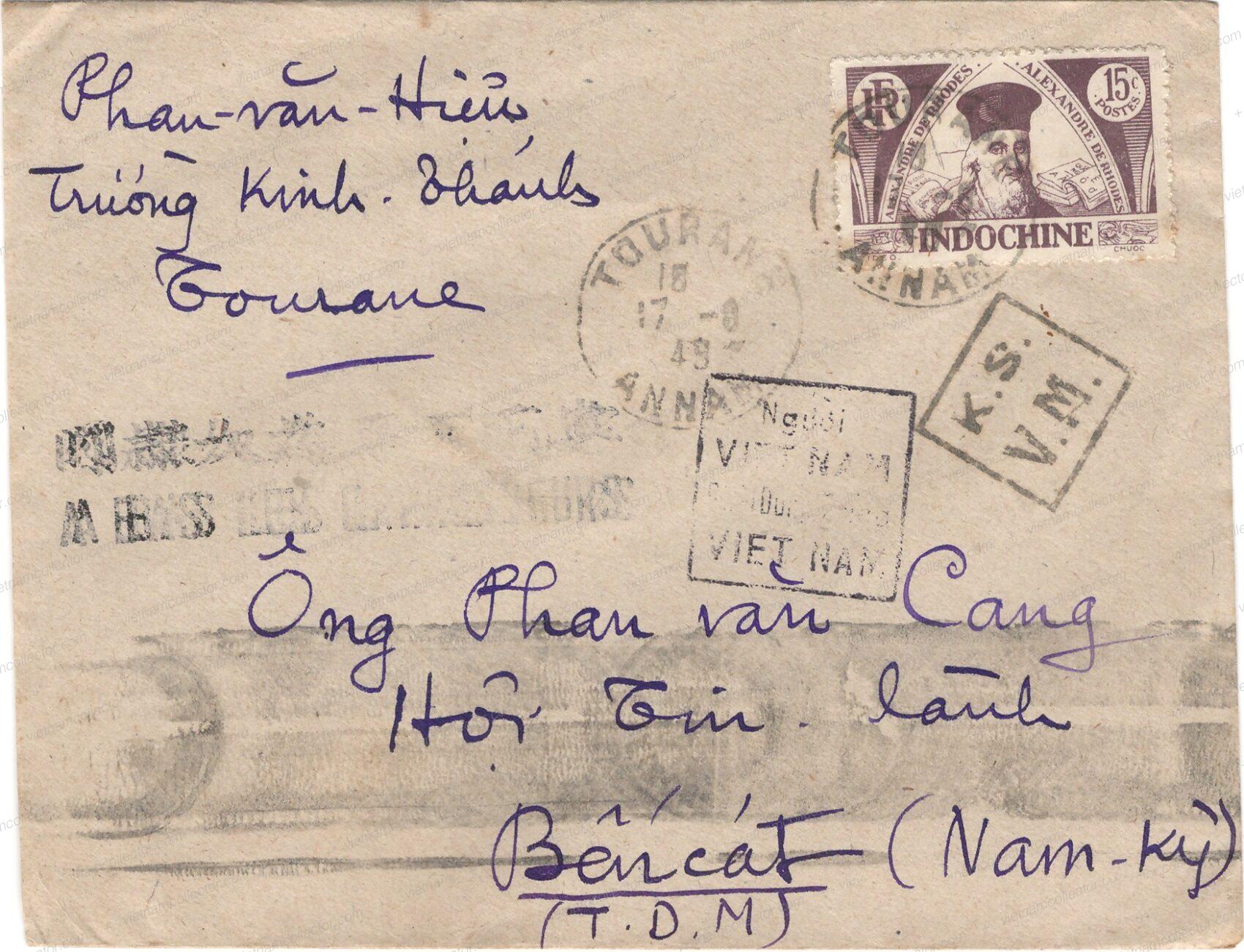

This is a domestic letter sent on August 17th, 1945 from Tourane to Ben Cat and that features three different Viet Minh markings. There are the propaganda cachets “Vietnamese only write in Vietnamese” along with the slogan “Down with the oppressors” in French and “Prefer Death to being a slave country” in Chinese. The letter was censored by the Viet Minh in Tourane where a boxed cachet “K.S. V.M.” was applied. These censure markings, which were produced locally and vary in appearance are very rare.

This is another letter was opened and censored by the Viet Minh. It was mailed on September 12th, 1945 from Tourane to Thu Doc. It is properly franked with 15C and carries the Tourane boxed K.S.V.M censorship cachet. Very rare.

Domestic letter sent from Bac Lieu to Cholon on August 22nd, 1945. The letter is properly franked with 15C and carries the pseudo Daguin “Vietnamese only write in Vietnamese”.

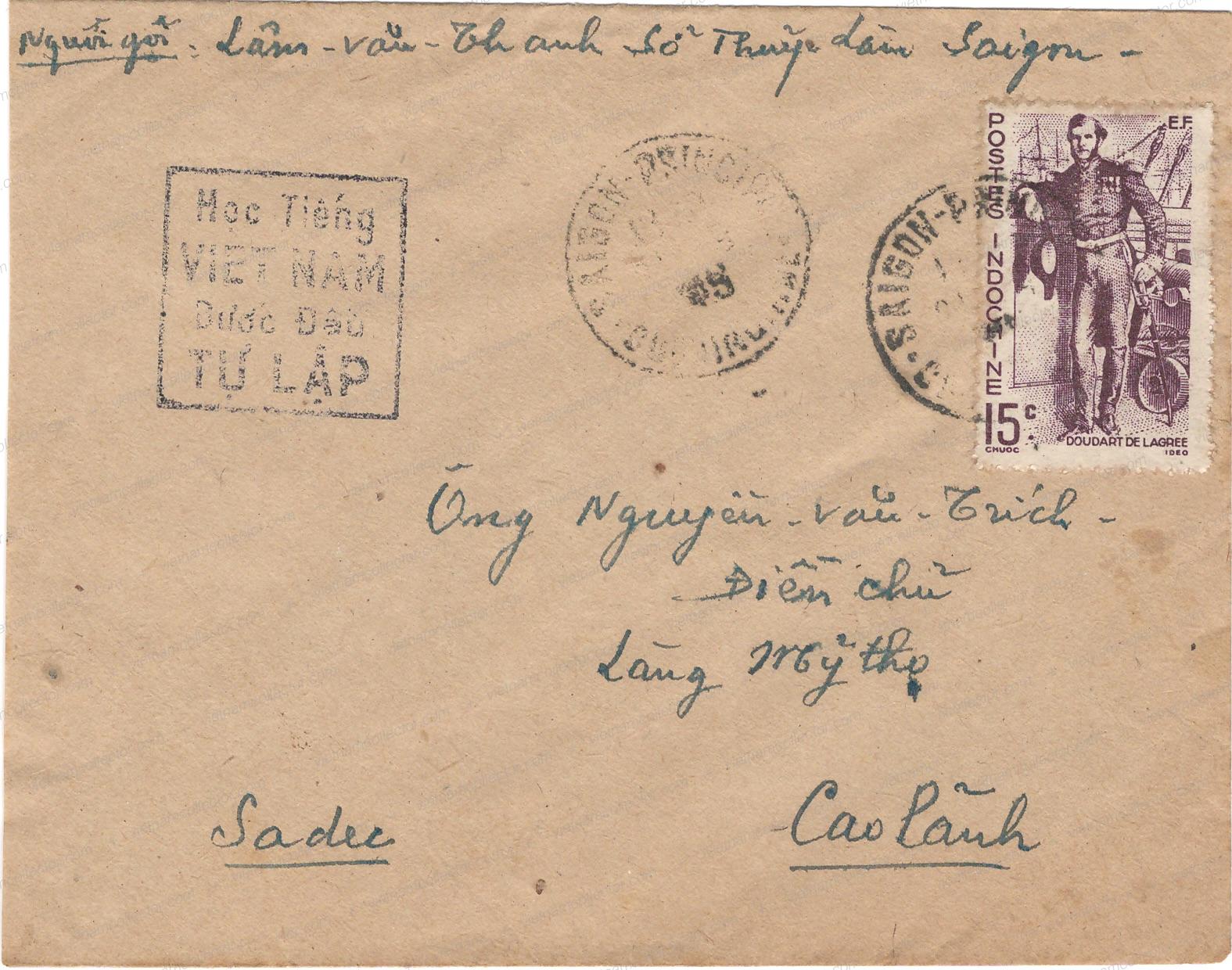

Domestic letter sent from Saigon to Cao Lanh in September of 1945 properly franked with a 15C de Lagree stamp and carrying the pseudo Daguin “Hoc Tieng Viet Nam Duoc Day Tu Lap” which means “Learning Vietnamese is the first step towards independence”.

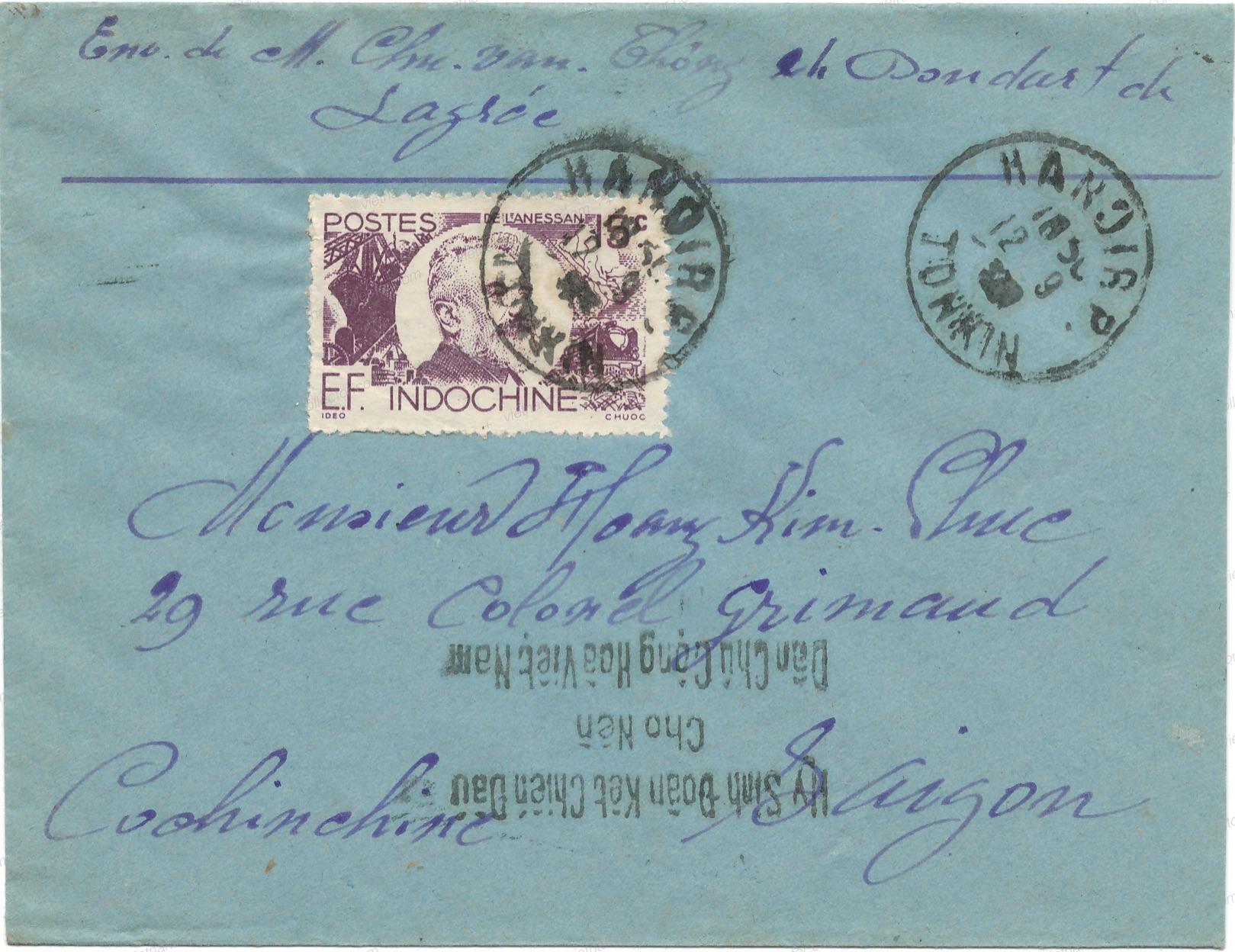

Single franking of the 15C L”Anessan stamp paying the correct domestic letter rate at the time on a mailing from Hanoi to Saigon on September 12th, 1945. The letter carries the rare “Hy sinh Đoàn kết Chiến đấu cho nền Dân chủ Cộng hòa Việt Nam” Viet Minh propaganda cachet that translates to “Ready to sacrifice to fight in solidarity for Democracy for the Republic of Vietnam”. Hanoi transfer cancel from September 14th, 1945 on the reverse.

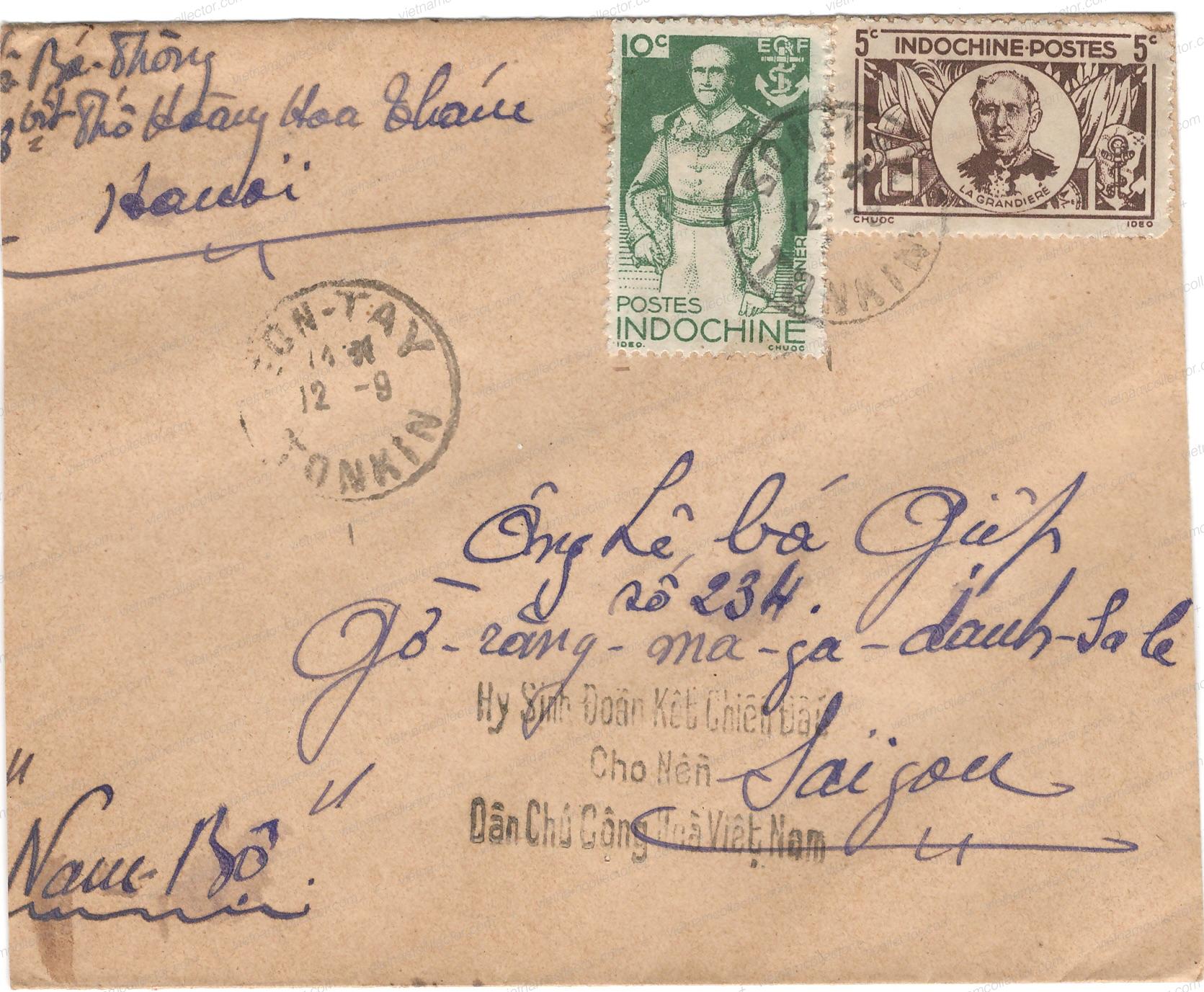

Mixed franking of the 10C Charter and 5C La Grander stamps from the same date (September 12th, 1945) paying the correct domestic tariff of 15C and sent from Son Tay to Saigon. The letter carries the rare “Hy sinh Đoàn kết Chiến đấu cho nền Dân chủ Cộng hòa Việt Nam” Viet Minh propaganda cachet that translates to “Ready to sacrifice to fight in solidarity for Democracy for the Republic of Vietnam”.

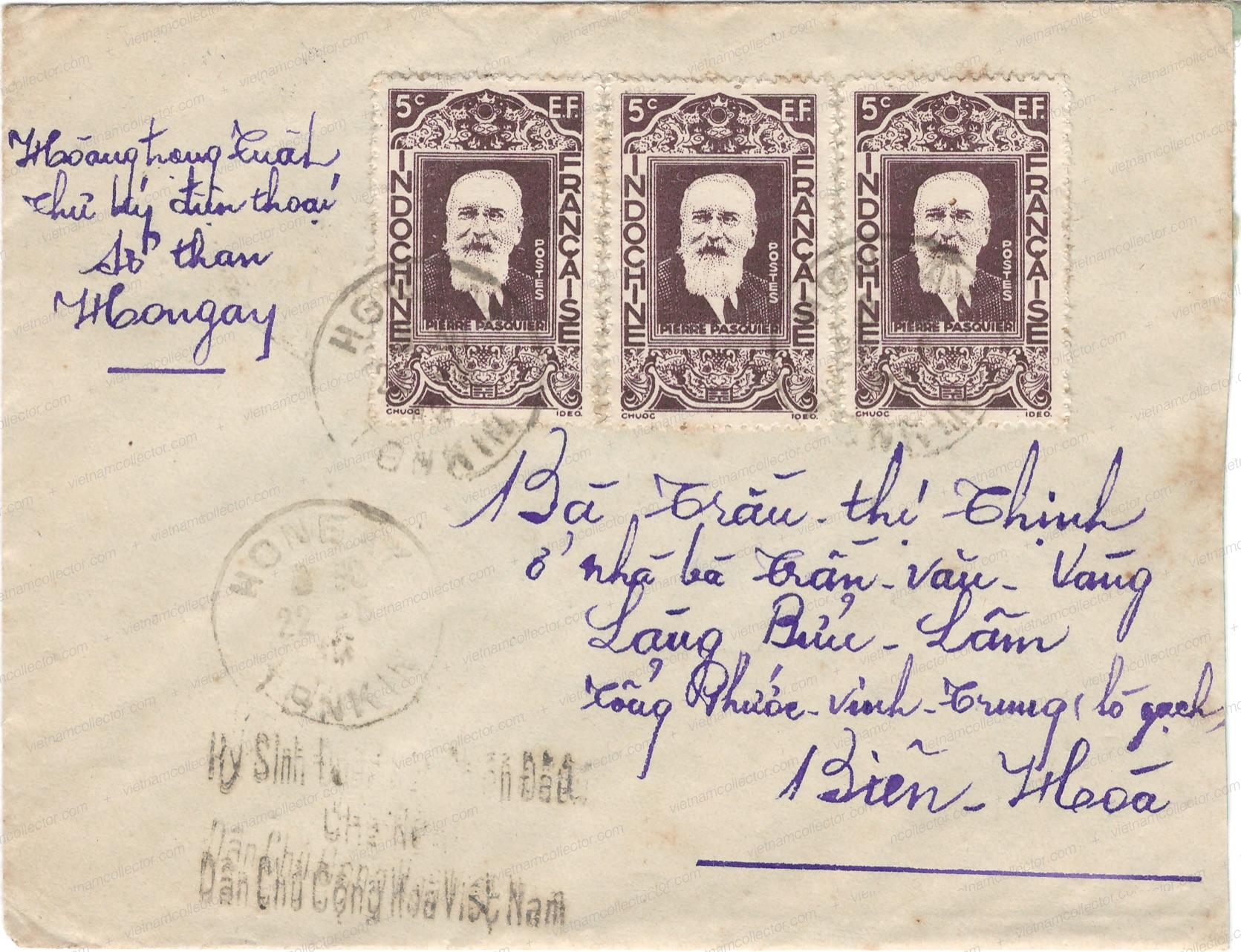

Multiple franking of the 5C Pasquier stamp (3) paying the correct domestic letter tariff of 15C on a letter sent from Hong Gay to Bien Hoa. The letter carries the rare “Hy sinh Đoàn kết Chiến đấu cho nền Dân chủ Cộng hòa Việt Nam” Viet Minh propaganda cachet that translates to “Ready to sacrifice to fight in solidarity for Democracy for the Republic of Vietnam”. Hanoi transfer cancel on reverse.

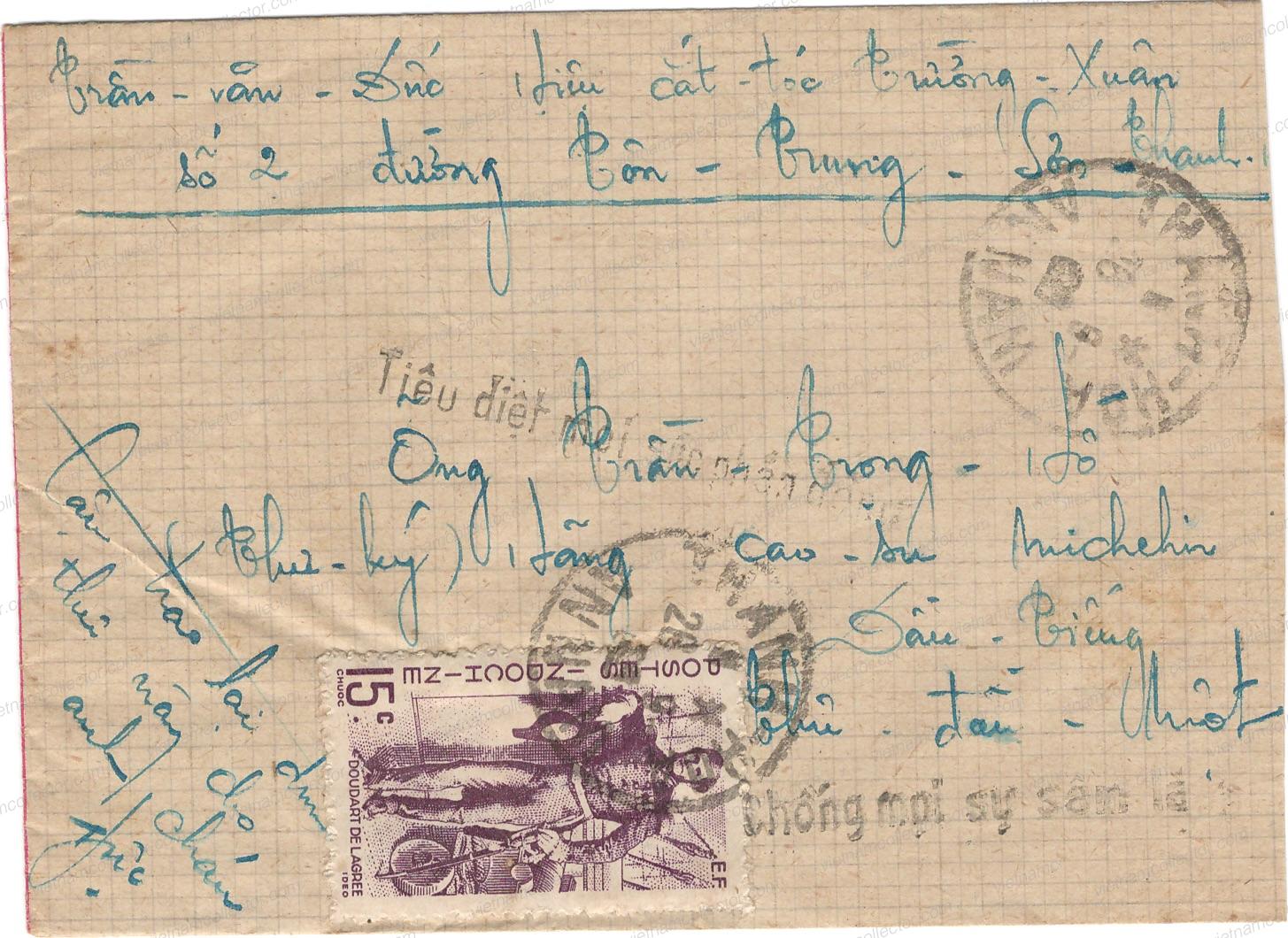

Single franking of the 15C De Lagree stamp paying the correct domestic letter rate at the time on a mailing from Than Hoa to Chu Tan on September 26th, 1945. The letter carries the rare Viet Minh propaganda cachet that state “Tiêu diệt mọi sức phản động, chống mọi sự sâm lăng” which translates to “Destroy all reactionary forces, against all aggressions”.

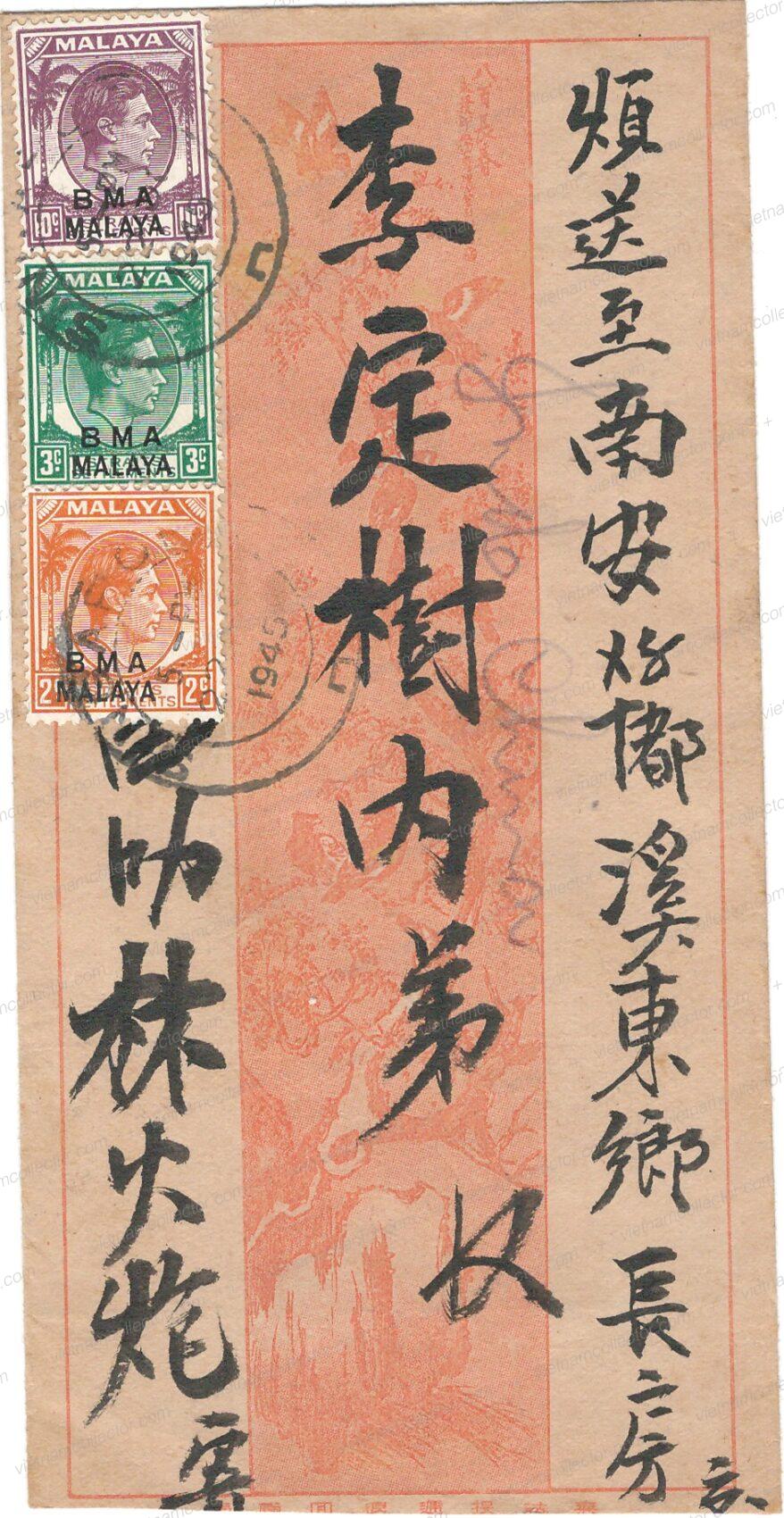

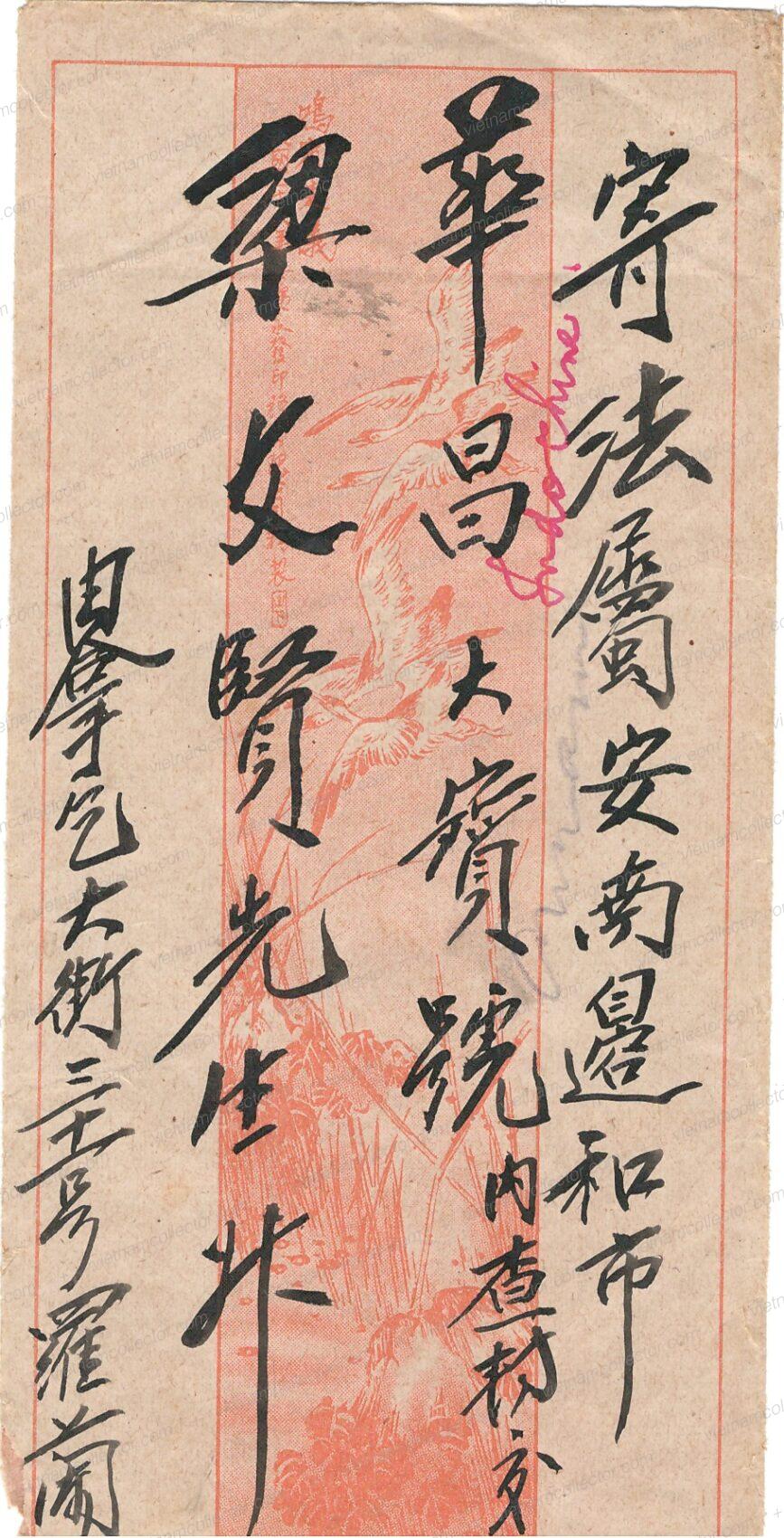

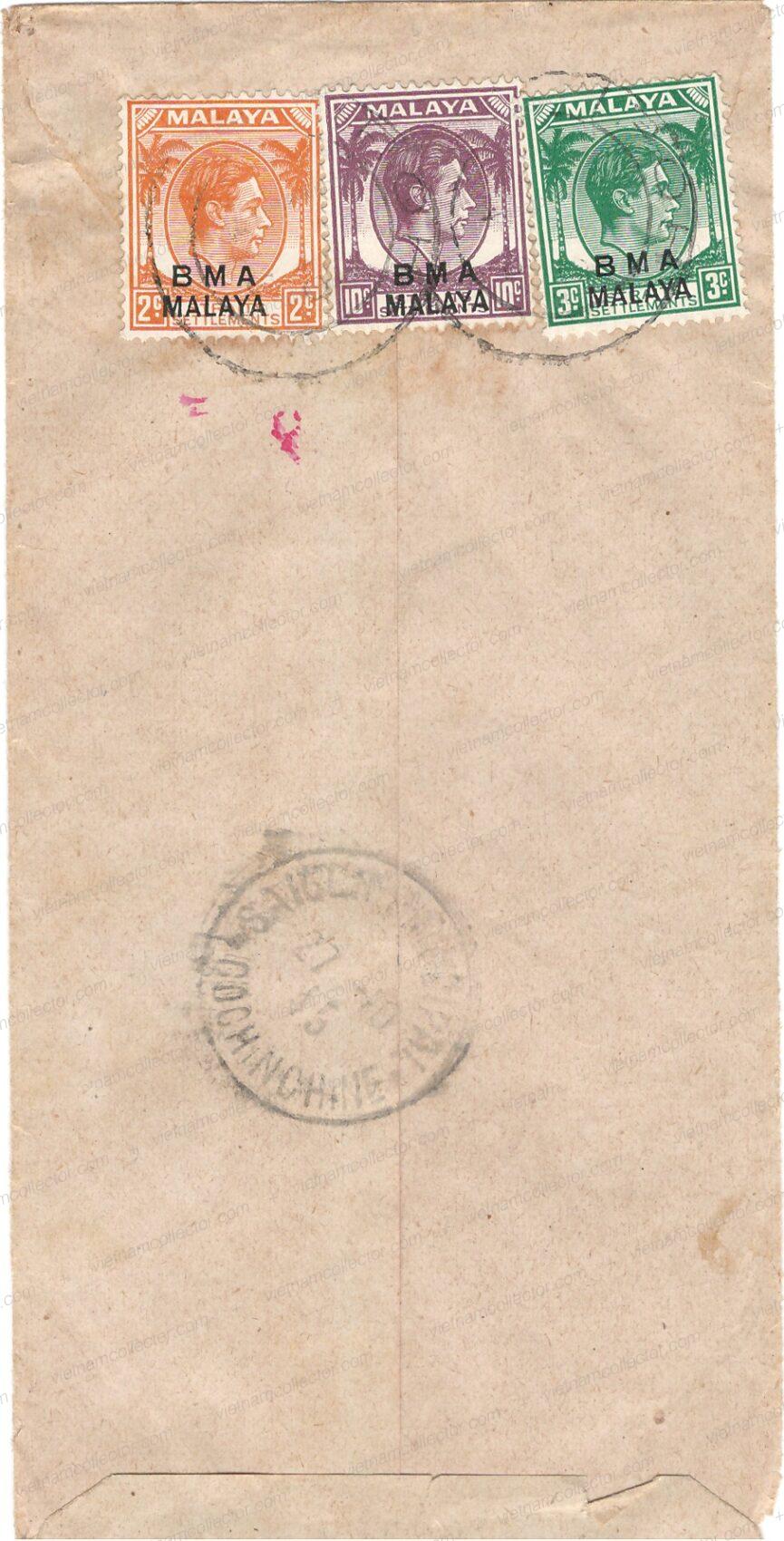

Below are two international letters that were sent from Singapore to Kampong Chan in Cambodia. They were both sent on October 27th, 1945 a time when both Singapore and Indochina had already been freed from the Japanese occupation. They demonstrate that the incoming international traffic routes were already active again shortly after the end of World War II.

Of course, a liberated France was not about to give up on its former colony. Shortly after the Japanese coup de Gaulle took diplomatic action. He requested the assistance of the Allies to build up a French resistance movement in Indochina. [10]

The main objective being access to Allied shipping capacity that would enable troop and weapon movements. However, at that time the United States under Rooseveldt was non-comital. He felt that Indochina should be liberated from colonialism. Rooseveldt died on April 12th, 1945 but his influence on policy was still latently present when it was decided at the Potsdam Conference in July/August, 1945 that Indochina should not be liberated by the French but by British Forces south of the 16th parallel including Cambodia and the Chinese north thereof including most of Laos. In the last days of August, 1945 150,000 Chinese troops under Chiang Kai-Shek crossed the northern border and they entered Hanoi on September 9th to take charge and disarm the Japanese soldiers. The British (Nepalese Gurkhas and Muslims from the 20th Indian Division numbering less than 1,000) arrived a few days later, on September 12th and started doing the same in Saigon. However, it took until September 22nd before the imprisoned French troops were finally released, who, now re-armed, a day later, started an insurrection against the Vietnamese Nationalists.[11] Many historians consider September 23, 1945 as the start of the French-Indochinese War. By that time, the United States under its new president Truman had changed her mind. Worried that The French may politically move into the camp of communist Russia they decided it would be the lesser evil to allow the French to recolonize Indochina after all. The French battleship Richelieu and the light cruiser Triumphant arrived on October 3rd in Saigon and the 5th Colonial Regiment from Sri Lanka disembarked. The 2nd French Army Division arrived in late October. The 9th Colonial Division arrives shortly thereafter aboard eight American ships. By the end of the year, fanning out from Saigon, the French controlled most of Indochina south of the 16th parallel.[12]

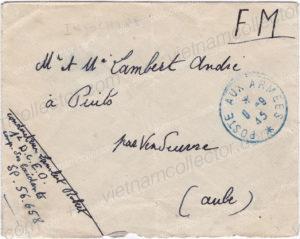

Desrousseaux reports in SICP Journal 13 that the first French military post offices (BPM) were set up in October in Saigon and November in Hanoi. The troops used a “mute” Poste aux Armees” cancel with two six pointed stars (pictured in his article as Figure 138). The letter above shows this cancel but with a date that makes it unlikely to have been used in Indochina, as all French troops were still imprisoned at that time. Fellow SICP member Ronald Bentley pointed out that these type of cancels were essentially “mobile cancels” that traveled with the respective troop unit. So, it is possible that the letter was sent as the soldier was in route to Indochina or from a French army unit not connected at all to Indochina but using the same “mute” canceler in the field. For that, the once secret field post address “S.P. 56.658” would have to be decoded and the author has been unable to do so. May be another collector has some information regarding this or knows where the 1st D.C.E.O. Corps des Exidants” was operating in early September, 1945. The first French plane that left, after dropping off General Leclerc on the 5th, left on October 6th.[13]

Desrousseaux reports in SICP Journal 13 that the first French military post offices (BPM) were set up in October in Saigon and November in Hanoi. The troops used a “mute” Poste aux Armees” cancel with two six pointed stars (pictured in his article as Figure 138). The letter above shows this cancel but with a date that makes it unlikely to have been used in Indochina, as all French troops were still imprisoned at that time. Fellow SICP member Ronald Bentley pointed out that these type of cancels were essentially “mobile cancels” that traveled with the respective troop unit. So, it is possible that the letter was sent as the soldier was in route to Indochina or from a French army unit not connected at all to Indochina but using the same “mute” canceler in the field. For that, the once secret field post address “S.P. 56.658” would have to be decoded and the author has been unable to do so. May be another collector has some information regarding this or knows where the 1st D.C.E.O. Corps des Exidants” was operating in early September, 1945. The first French plane that left, after dropping off General Leclerc on the 5th, left on October 6th.[13]

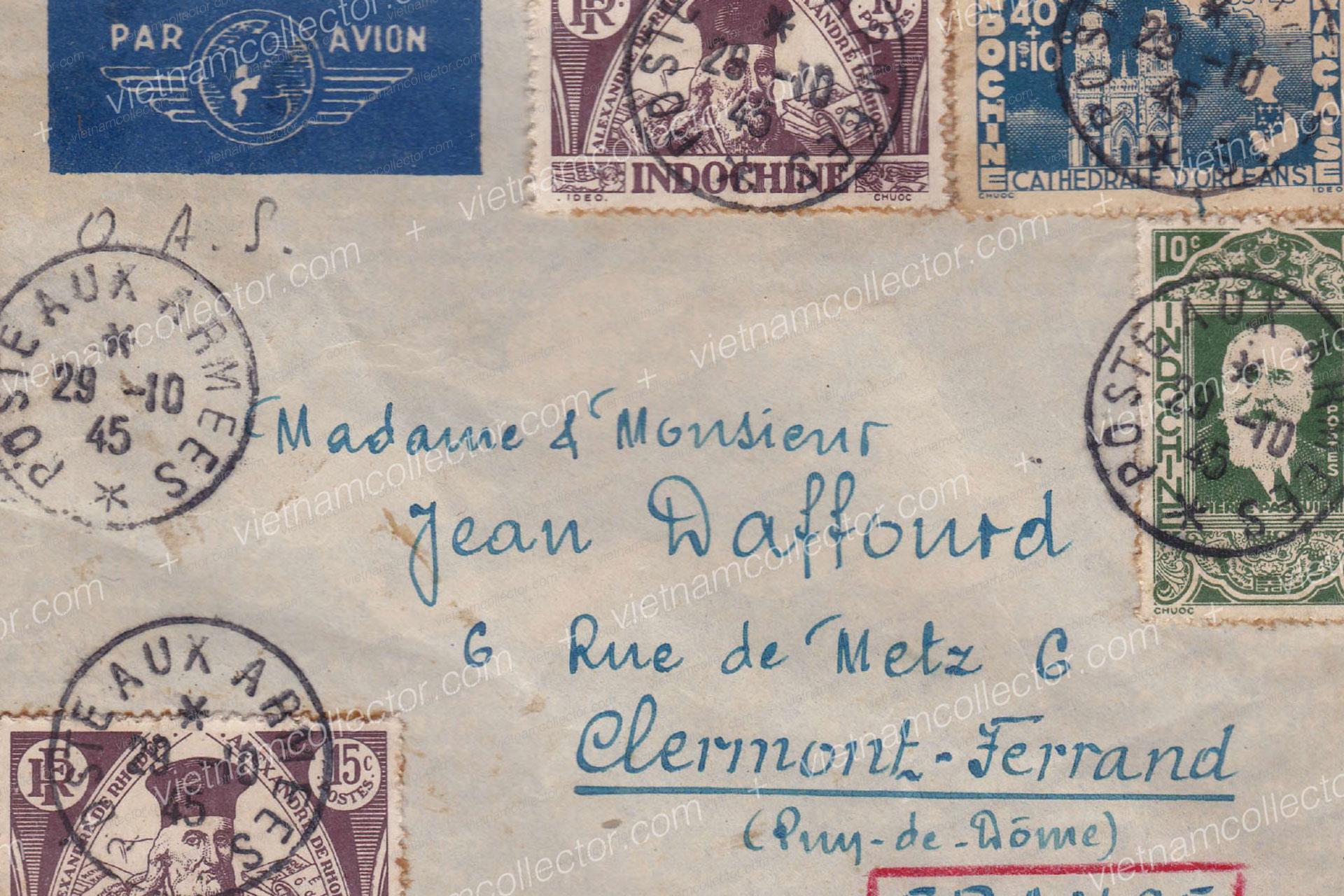

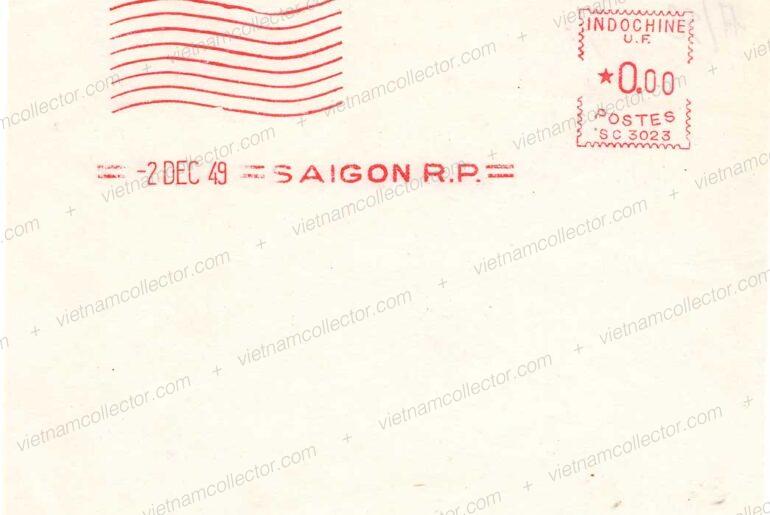

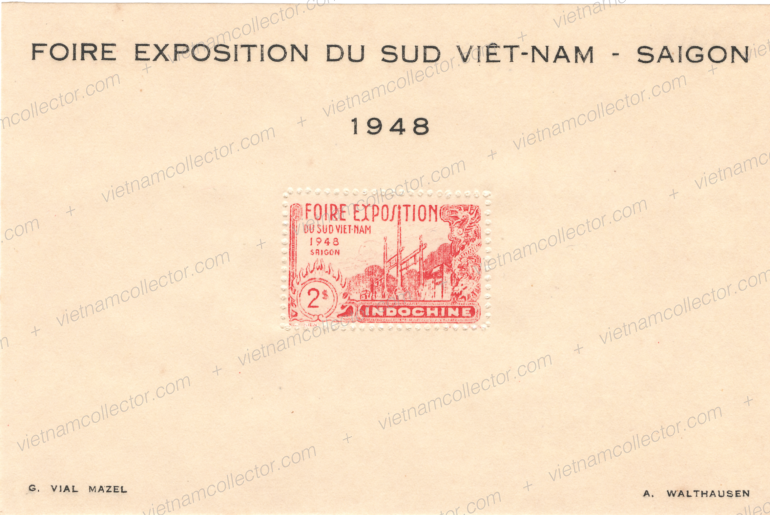

So theoretically it may have carried back mail to France. However, the earliest civilian cover in the authors possession that documents the re-starting of civilian mail in Saigon is dated October 26th, 1945 (see letter above). It has a civilian Saigon cancellation. For Phnom Penh (Cambodia), as identified by the senders address on the back, the earliest date is October 29th but here the military carried out the mail service as it is cancelled with the “mute” Postes aux Armees” canceller already described earlier (see second letter above).

The mobile military cancel must have been in operation only for a few weeks as the letter below shows. This letter, directed to Metz in France was mailed on December 25th, 1945 and it was cancelled with a Post aux Armes cancel that carried the addition “T.O.E.” at the bottom.

It would be interesting to see if other collectors have mail that documents earlier dates for South Vietnam and Cambodia or military mail that is clearly from Indochina and that documents the opening of the BPO’s in Saigon and Hanoi in October and November of 1945. Also, what is the earliest date in your collection that documents the opening of the postal route from Laos after the war? Please send any input to the editor.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_France

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_invasion_of_French_Indochina

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_invasion_of_French_Indochina

[4] J.Desrousseaux; SICP Journal Nr. 13, August 1973

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vichy_France

[6] F.Logevall, Embers of War

[7] J.Desrousseaux; SICP Journal Nr. Nr. 12, June 1973

[8] S.Tonnesson, Vietnam 1946, How the war began

[9] S.Tonnesson, Vietnam 1946, How the war began

[10] S.Tonnesson, Vietnam 1946, How the war began

[11] S.Tonnesson, Vietnam 1946, How the war began

[12] F.Logevall, Embers of War

[13] J.Desrousseaux; SICP Journal Nr. 13, August 1973

Comments are closed.