sAfter the spring military offense in 1975 that culminated into the fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975, the North Vietnamese Government, as what many authoritarian regimes tend to do, consolidated its power among the South Vietnamese population. Former supporters of the Republic of South Vietnam (RSV), which were inherently dangerous to the new Government, had to be controlled and/or reeducated to properly drum the party line.

The Basis

The basis for this reeducation was already established on June 20, 1961, when the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) enacted Resolution 49-NQTVQHN in order to deal with “counterrevolutionary” elements of society, after Ho Chi Minh took total control of North Vietnam from the French, and also had some dissatisfied parts of the population to deal with that required pacification. This resulted in the establishment of reeducation camps in the North, set up to deal “with the task of concentrating for educational reform counterrevolutionary elements who continue to be culpable of acts which threaten public security.” (The Indochina Newsletter October-November 1982) This resolution was quickly applied to South Vietnam after the DRV’s takeover. This article only deals with camps that were set up from 1975 and thereafter. Already in May, 1975, various groups of South Vietnamese were ordered to report themselves to the new Government. These groups included:

-former SVN military-, security- and intelligence personnel of all ranks

-members of executive, judiciary and legislative branches of the Republic of Vietnam (RVN) Government

-members of non-communist political parties

-members of religious sects

In June of 1975, these groups were ordered to attend reeducation at various locations. Depending on their assessed threat to state security, the individuals were allocated into two groups of reeducation:

-Group 1, soldiers, non-commissioned officers and former Government rank and file employees, who were supposed to attend a three day reform study from June 11 through June 13 that allowed them to return home in the evenings and

-Group 2, all the rest of the people who were supposed to participate in 24 hour reform studies until “the course ended”. This was indicated to be for no longer than a month.

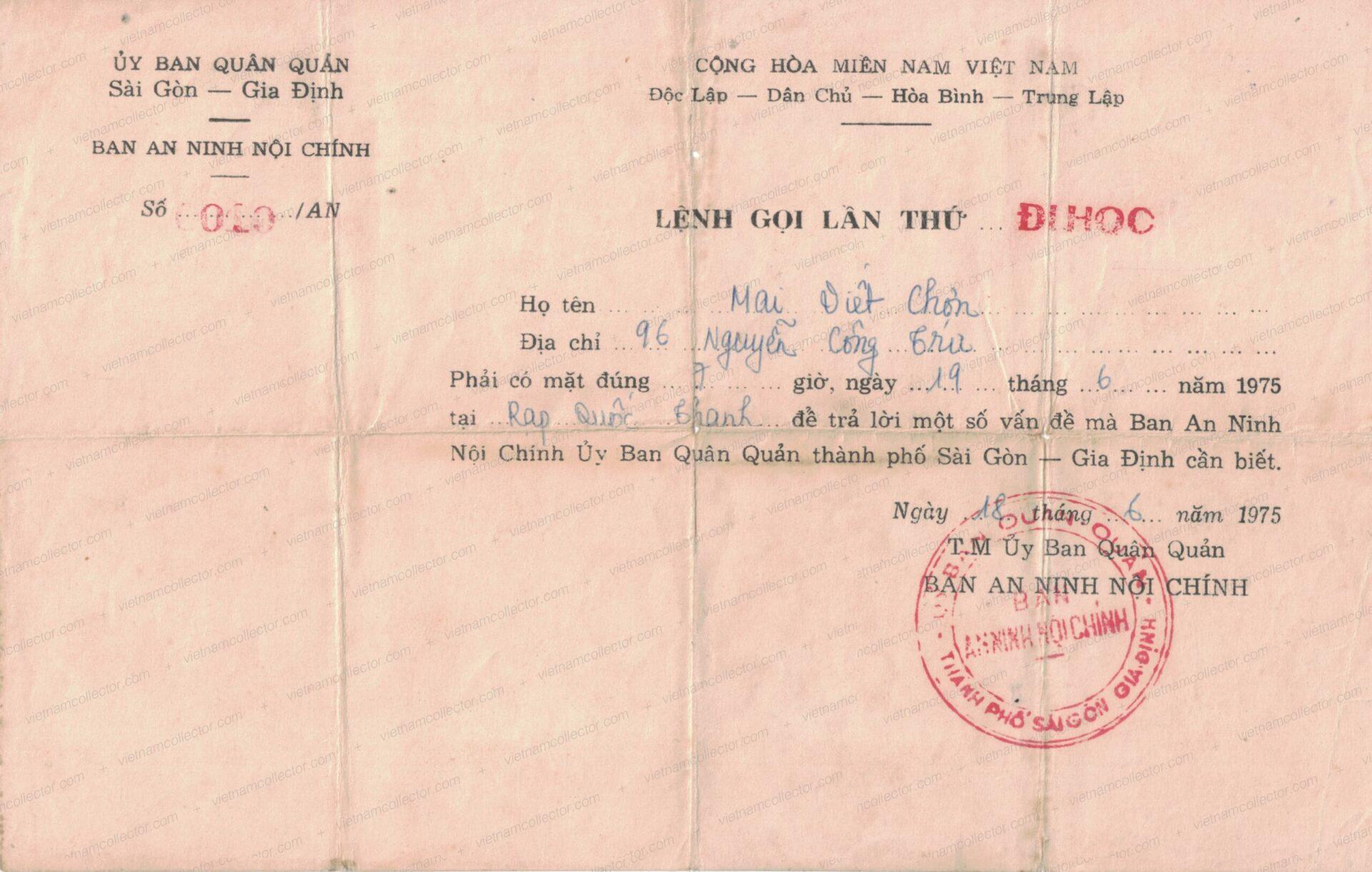

Here is a sample of an “invitation” of the Military Administration Saigon-Gia Dinh, Commitee of Interior Security to Mai Viet Chon, living at 96 Nguyen Cong Tru, to appear on June 19th, 1975 in the cinema Quoc Thanh, in order “to answer a number of questions” of the Committee for Interior Security (the document is not part of the collection and was provided by courtesy of Cường Mai Viết). Mai Viet Chon was a member of the South Vietnamese Police force and hence inherently suspicious to the new regime. According to his grandson he got lucky though and was released after only 3 days of reeducation.

Participants were requested to bring necessary items such as personal effects, food and money. This was to last for 10 days for Group 1 and one month for Group 2 participants. Similar to the Jews in Nazi Germany who were sent to concentration camps, participants were told that everything beyond that immediate need, including medical assistance, was provided on site.

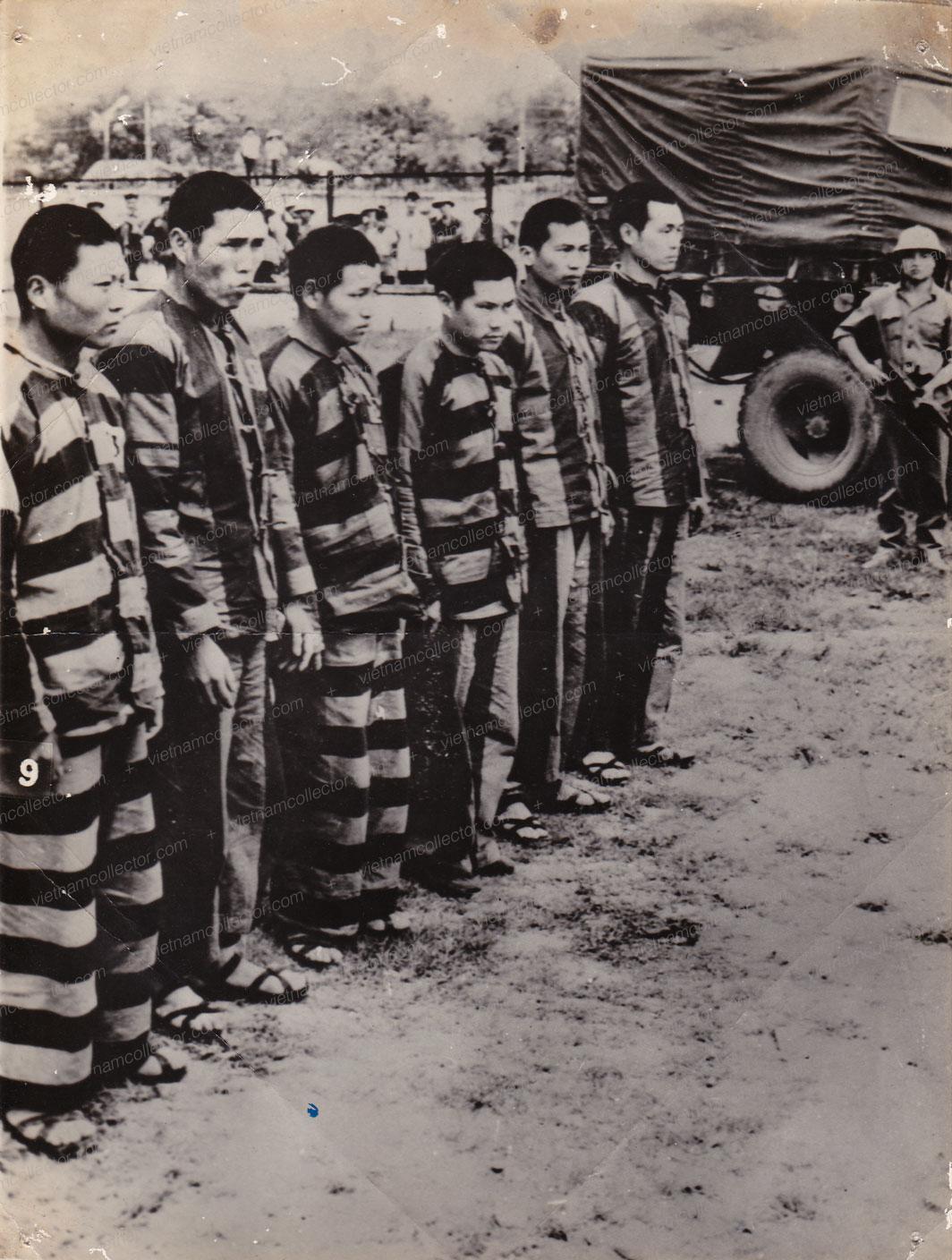

Below is an original photograph of prisoners within a reeducation camp

Given the short duration of the proposed reeducation, many people, such as teachers, doctors and even sick people, who were not required to report, volunteered themselves to be reeducated, because they believed that they would have to undergo the classes later on anyway, or because they were hoping for immediate medical attention.

Hope of early release

Needless to say, all of this was a ruse to pacify “school” attendees and family members left at home in order to avoid defections, public protests or even a public uprising. Very few of the people that registered were released within the promised time frames. Most of the lower threat people spent a number of months in the camps, with many being released by the end of 1975; while the higher threat ranks, such as military officers, higher ranked police officers and intelligence personnel ended up there for anywhere between three to twelve years. A few thousand inmates served even longer sentences presumably because they were still considered to be counterrevolutionaries. In the early phase of the reeducation campaign, the emphasis of the camps was political indoctrination and written confessions. As is typical for investigators worldwide, confessions were taken over and over again to see if a person’s story would change. People who confessed to alleged crimes (Mail clerks, for example, were told that they were guilty of aiding the ‘puppet war machinery’ by circulating the mail) and therefore showed contrition, were given hope of early release. Of course, apart from political realignment, the intent of these confessions was also to implicate other people, who had not reported to the Government by either going into hiding or fleeing the country. This, in turn, spawned continuous new arrests. Many intellectuals, writers and poets were swept up in these secondary campaigns. Lacking precise data from the DRV, the estimates, of people having attended the camps ranges from 1 to 2.5 million. They were housed in about 80 labor camps, often arranged in clusters of three to twelve sub-camps, spread around the country. All in all, there may have been close to 1,000 individual camp locations at one time. Camps in these clusters were three to five miles apart, but longer distance camp affiliations have been reported. The exact number of the camps remains unknown as some of them were combined over time or simply closed. Group 1 low threat attendees ended up in camps that were in remote locations in South Vietnam (often near a town or village that was pro National Liberation Front (NLF) prior to the fall of Saigon) and Group 2 individuals ended up in camps in North Vietnam, often close to the Chinese Border. Most inmates were rotated between three to five different camps in order to avoid fraternization among inmates and guards. The location of the prisons was initially kept secret in order to avoid “counterrevolutionary” discussions among the population at large, but also to avoid family members aiding in the escape of prisoners. As a result all the mail from guards and inmates was handled using the military postal system using Hòm thư Numbers.

Later on, the economic situation of the country required a bit more openness as the support of family members was becoming crucial to keep inmates alive, due to the lack of food and clothing.

The camps later emphasis was clearly on hard labor and less of political indoctrination, as the DRV followed Mao Tse Tung’s example of the Cultural Revolution. Physical labor was supposed to discipline prisoners and to prepare them for more menial tasks after their release. Given their past political affiliation, the DRV no longer considered these people “leader material” and was getting them ready for support positions.

Conditions were very harsh

The labor involved farming, providing supplies for the camp and clearing jungle for agriculture; but, on occasion, also clearing minefields, barehanded. The food supply was poor to begin with, and worsened over time as economic conditions in the whole country deteriorated. Most inmates received only one serving of rice, the size of an orange, per day, with the occasional vegetable mixed in and some water (Vietnamese Re-Eudcation Camps: A Brief History by Quyen Truong). Meat was virtually nonexistent and was only served on big national holidays, such as Ho Chi Minh’s Birthday. People were housed in huts with a slightly elevated bamboo floor, 60-70 prisoners per hut, with each one allowed two hand spans of space on the floor. Each inmate received just one pair of pants and one shirt per year. Medical attention was virtually nonexistent other than that provided by fellow inmates who were incarcerated doctors. Very few people were allowed to leave camp for medical treatment. Visits by family members were initially limited to one per year, and that only lasted 30 minutes to one hour. As of 1980, up to four visits by immediate family were allowed, to improve the food supply to inmates. Visitors were interrogated for about 30 minutes prior to being allowed to see their loved-ones. There was no physical contact during visits and a guard was present within earshot at all times. Punishments for violating the camp rules, such as eating vermin caught in the camp as supplemental protein, included beatings, various means of torture and in case of attempted escape, the death penalty. Given poor nutrition, hard labor under the tropical sun, and suicides, disease and death was widespread. An estimated 165,000 of the inmates died (Wikipedia); often without their family being notified.

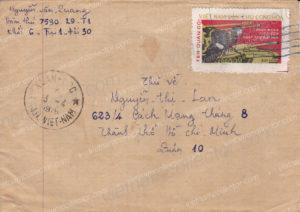

Inmates were allowed to write home every 1-5 months. Guards could, of course write as many letters they wanted by using military free franks or civilian postage. Similar to NVN military mail, the location of the labor camp was mostly obfuscated by an alpha-numeric code, sometimes used in conjunction with a military Hòm thư (“HT” = letter box) number. In fact, the camps were administered by the DRV military or the National Security Services, and sometimes, by both of them. The code usually shows the code for the main camp first (i.e. T1) first followed by the code for a subordinate sub-camp (i.e.L6), followed by the unit number (“Doi”) the prisoner was housed in. The address of the camp also included the province and, of course, the name of the prisoner. Recognizing these codes is often the only way to determine if a letter falls under the category of camp mail. The guards of the camps also acted as censors, though typically no censor marks were applied to the envelopes (Information provided by former SICP member Bob Munshower). There are few exceptions, as some covers have been found to contain manual notes by guards. There is at least one particular case from an agricultural camp (Nong Troung – Information provided by fellow member Lucian Lu) in Hau Giang Province where a red censor stamp with three lines in italics reading “Kiem-Duyet” (which means “Censored” or “Examined”), along with a date line and the signature of the guard was applied to the back of the envelope. (Information obtained from notes in the NVN military collection by SICP member Jack Dyckhouse/Joe Cartafalsa) (Exhibit 1) These are exceedingly rare.

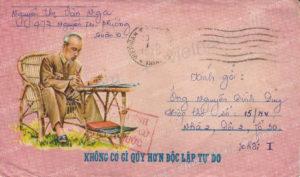

The inmate would write the letter, which included the address it was supposed to go to. The guard would inspect it for political correctness or hidden messages. If the letter contained improper information it was either thrown away or sometimes inserted into the camp file of the prisoner to justify later punishment. If the letter passed muster, the guard would insert it into the envelope that he/she addressed (for that very reason the writing on the letter and the writing on the envelope is often different) and insert it into a mail pouch. The pouch would then be transported using the military postal system to the post office of a large city closest to the camp and cancelled with date cancellers, again to obfuscate the real origin of the letters. Initially these letters were transported for free, similar to military or disabled-veteran mail. Of course, no official free-frank stamp was printed, as that would have provided too much attention indicating that these camps actually existed. Instead, the envelopes simply carry the handwritten term “Mien Phi” which basically means “Free” (Information provided by SICP member Frank Duering) but many a times no specific annotations were made as it apparently was understood within the postal system that no postage was due for these letters . That was the case for both outgoing letters and mail that was sent by relatives to the camp (Exhibit 2 and 3). Incoming mail is quite rare, as very few inmates were able to preserve letters and envelopes under the difficult environmental conditions during their long period of incarceration. Incoming letters to prison guards are more numerous.

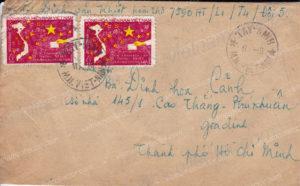

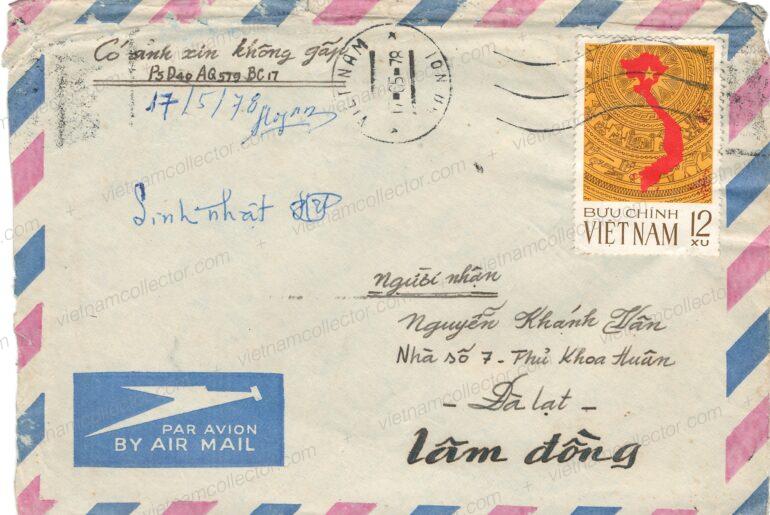

This postal regulation apparently changed later on, as all the un-franked letters in possession of the author date to about 13 months after the initial set-up of the camps in June, 1975. Most later letters have regular NLF or DRV postage stamps attached at the regular standard letter rate but some postage free letters (probably from guards) can one found as late as 1980. Postal clerks were often confused which type of military letters were to be treated as postage free (usually unit to unit correspondence). The exact date of change of the postal regulation is not known to the author, but the first franked letter in the authors collection dates from October 1976 (Exhibit 4). The free-frank period, therefore, could not have lasted for more than 15 months in total. Needless to say, free-frank camp letters are very rare due to the limited period they were actually possible. Any additional information that the membership may be able to provide as to the postal regulation change is highly appreciated. This change may have been a result of the deteriorating economic conditions in the country as a whole. The country simply no longer wanted to afford to transport these letters for free as a general re-thinking in the status of the inmates had taken place. Initially, the DRV had not considered people in reeducation camps as criminals, but changed that position later on when they labeled all of them as “war criminals” in order to defend the Government position against international human rights groups. These groups correctly claimed that the reeducation camps were a violation of Article 11 of the Paris Agreements which guaranteed the Vietnamese People freedom from reprisals and discrimination of those who collaborated with one side or the other during the war.

Since none of the camps had any postal facilities (Information provided by former SICP member Bob Munshower), inmates who later on required stamps, had to purchase them from the guards with funds obtained from relatives. Guards often charged a multiple of the stamp’s face value for their services.

Guards were part of the military or secret police and hence enjoyed military free-frank privileges. That means all letters from reeducation camps that carry military free-franks are from camp guards (Exhibit 5).

Prisoners were also allowed to receive two “gifts” per year. One was usually handed over to the guards during a personal visit, the other was sent by parcel mail. These packages, that mostly contained food items, were rather critical in the later years of the camps to keep inmates alive. To date, the author has yet to see a single parcel front of a parcel sent to the camps and it is very likely that none exist anymore. This has to do with the fact that the guards were the ultimate arbiters of what a prisoner would actually receive. They would open the package in order to determine what they wanted to hand to the inmate and what they wanted to keep for themselves. Items confiscated by the guards were officially “thrown away”; but in reality, they mostly ended up on the guards’ table as they also received very few provisions. In that process, the wrapper was simply thrown away or reused as kindling. Should one ever turn up, it would be a great modern philatelic postal history rarity. If you do have an example, the author would be grateful for a scan or photo copy.

Given the secrecy with which the NVN Government cloaked the system of reeducation camps, it is not surprising that information about the camps and the code designation they held is difficult to come by. The names of reeducation camps can sometimes be gleaned from reports of Human Rights Organizations (i.e. Dart Center for Journailsm & Trauma) (Camp Z30D: The Survivors by Anh Do, Tran Phan and Eugene Garcia) that reported the death or release of a particular prisoner. The best information, though, comes from the declassified files of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Though focused on identifying and locating American soldiers missing in action, they nevertheless list many camp names, camp locations, camp codes and numbers of inmates held. It is from these reports and information provided by former Military Police Officer Bob Munshower, that the author has compiled a list of identified camp codes and camp names. The list is clearly only a beginning and more work is needed to complete and, in some instances, probably correct it. Nevertheless, this is the first time that detailed information, allowing the identification of reeducation camp mail is offered to the philatelic community. Hopefully, this will enable fellow collectors to recognize these rather scarce letters and prevent them from perishing.

So, the next time you see a Vietnamese cover that carries an unusual alphanumeric code in the addresses or that is not franked, but obviously passed through the postal system without any postage due penalty marking, take another look! If the letter is neither official domestic Government mail nor 1950’s military mail (both were free of charge), then you may be looking at a reeducation camp cover!

Many thanks to the annotated fellow SICP members and philatelic friends that contributed to this article.

Short Reeduction Camp Glossary

(Glossary terms and traslation provided by foemer SICP member Bob Munshower)

Trai = Camp

Don Vi An Ninh = Security Unit

An Ninh = Police

Tu Nhan = Prisoner

Trai Tu = Main Prison Complex

Cai Tao = Reeducation

Trai Phu = Area Subcamp

Bao Ve Trai = Camp or Security Guard

Khu Trai = Camp or Zone Area

Lien Trai = Intercamp

d/c or dia chi = Comrade

Camp Postal Code |

Camp Name/Location |

| 1 | Tien Lanh |

| 2 | Trai Cai Tai So Hai |

| 4 | Phu Son, Bac Thai |

| 5 | Ly Ba So, Than Hoa |

| 6 | Nghe Tin |

| 9A | Thanh Hoa |

| 14 | Yen Bai |

| 15NV | Long Thanh |

| 16NV | Thu Duc |

| A5 | Thanh Hoa |

| A6 | Yen Bai |

| A9 | Than Hoa |

| A20 | Xuan Phouc, Phu Yen Province |

| A30 | Phu Yen |

| A40 | |

| A90 | Khue Ngoc Dien |

| A91 | Buon Ho |

| AH8NT | Yen Bai |

| B4 | Than Liet |

| B5 | Dong Nai Province Prison |

| B6 | Bien Hoa City Jail |

| B7 | Bien Hoa, Soui Mau |

| B14 | Than Liet, Than Tri, Ha Dong |

| B34 | Sai Gon |

| Cam Thuy #5 | Cam Thanh |

| A | Nam Ha |

| C | Nam Ha |

| C2 | Minh Loung |

| C4 | Phu Son, Bac Tai |

| C5 | Minh Loung |

| C10 | Dien Bien Phu |

| C13 | Khe Sanh |

| CT6 | Nghe An |

| D3 | Phoc Long |

| E8C1 | Phuoc Long |

| E50 | Ngo Bo Lo Gach |

| F15 | Ben Tranh |

| General Camp 1 | Yen Bai |

| General Camp5 | Minh Loung,Van Ben |

| HT1248 | Suoi Mau or Tan Hiep |

| KAU Minh | Kein Giang |

| K1 | Nghe An |

| K2 | Thanh Phong, Thanh Hoa |

| K3 | Xuan Loc |

| K4 | Phan Trai Cai Tao |

| K5 | Vi Thanh, Choung Thien, Than Son |

| K7 | Nhan |

| K7N | Choung Thien |

| K12 | Hoang Lien Son |

| K16 | Xuan Loc |

| K18 | Ben Tre |

| K20 | Tra Ba |

| K21 | Than Phu district township |

| K22 | Than Phu district |

| K24 | Ben Tre Province |

| K26 | Cho Lach district |

| K30 | |

| K32 | |

| T52 | Ha Tay |

| KH6 | |

| Ky Son 1 | Tam Ky Quang Nam |

| L9T1 | Long Gia |

| LT1 (Lien Trai) | Song Ong Doc |

| LT2 | Son La |

| LT3 | Tran Phu |

| LT4 | |

| LT5 | |

| LT6 | Yen Bai |

| NT1 | Nghe Lien, Son La, Ky Son |

| NT3 | Nghe Tin |

| NT6 | Nghe Tin |

| T1L6 | Katum |

| T3 | Hoang Lien Son |

| T4 | Son La, Ka Tum |

| T5 | Thanh Hoa |

| T6 | Nghe Tinh |

| T7 | Kinh Lang Tu |

| T11 | Yen Bai |

| T14 | Yen Bai |

| T15 | Gia Lai |

| T18 | Nam Ha |

| T20 | Nam Ha, Pleiku |

| T82 | Saigon, Interrogation Camp |

| TH6 | Xuyen Moc |

| Z20A | |

| Z30A | Xuan Loc |

| Z30 | Ham Tan, Binh Thuan Province |

| Z30B | Gia Rai, Long Khanh |

| Z30C | Ham Tan, Thuan Hai Province, near Da Mai village |

| Z30D | Ham Tan, Thuan Hai Province, near Da Mai village |

Comments are closed.