Some of you may have wondered what the alpha numeric code in the address section of many Vietnamese letters addressed to Eastern Europe meant. Often, the letters will just show the name of the recipient, the numeric code and the city/country. Only occasionally would a street name or a factory name be included. So, it leads one to wonder, how were the mailmen in Eastern Europe able to deliver these letters to the intended recipient? I recently looked into this and this is what I found.

Due to the economic conditions in the former Eastern Block countries in the years following World War II, many people with job qualifications were looking for a better life in the West. As a result, the Eastern countries that shared a border with the West experienced a significant “brain drain”. This was especially pronounced in the former East Germany, which only came to a halt after the East German Government decided to build the “Berlin Wall”. The wall that started in Berlin soon expanded along the entire frontier of West Germany. By then, 3.4 million people[1] had already fled the country. This resulted in a severe labor shortage that East Germany and other Eastern European Governments had to address. The more advanced economies, such as East Germany, Hungary and Czechoslovakia entered into Government employment contracts in the early 1960’s with countries that were politically aligned. These countries included Angola, Cuba, Nicaragua, Mozambique, Poland and North Vietnam. The principal idea was to acquire labor for the consumer goods and light industrial sectors, such as textile factories. Of course, the exchange was officially not portrayed as the procurement of cheap labor, as this would have been contrary to socialist ideals but more of brotherly assistance in educating fellow socialists from developing countries. It is certainly true that many a contract worker received good job training during their stay, which assisted them later on in life. Some even acquired master degrees in certain trades but that was more a side effect than the primary objective.

The guest workers received contracts that ranged between two to six years and the rotation principle was strictly observed to avoid too great of an attachment. Family members were not allowed to join them. There was no intention of integrating these guest workers into society as they were expected to leave after their assignment, and, as such, they were kept isolated from the general populace. They lived in housing facilities that were either directly attached to the factory they worked at, or close by. Contact between the guest workers and the general population was not desired; and, in order to ensure this, the comings and goings of guest workers from their housing facility was strictly controlled. In order to ensure better isolation, all workers were subject to a curfew when they had to be back in the housing facility, which was often located outside of town. Visitors to the facilities had to be announced and had to leave the facility by the curfew; and it was expected that a report to the Secret Service was made after the visit took place. Female guest workers that became pregnant during their stay faced automatic expulsion from the country or were cajoled into having abortions. Also, workers who did not meet their production quota or who violated socialist principles (whatever that means) were expelled. Travel back home was principally possible but often economically impossible, as most workers sent much of their earnings home in order to assist family members.

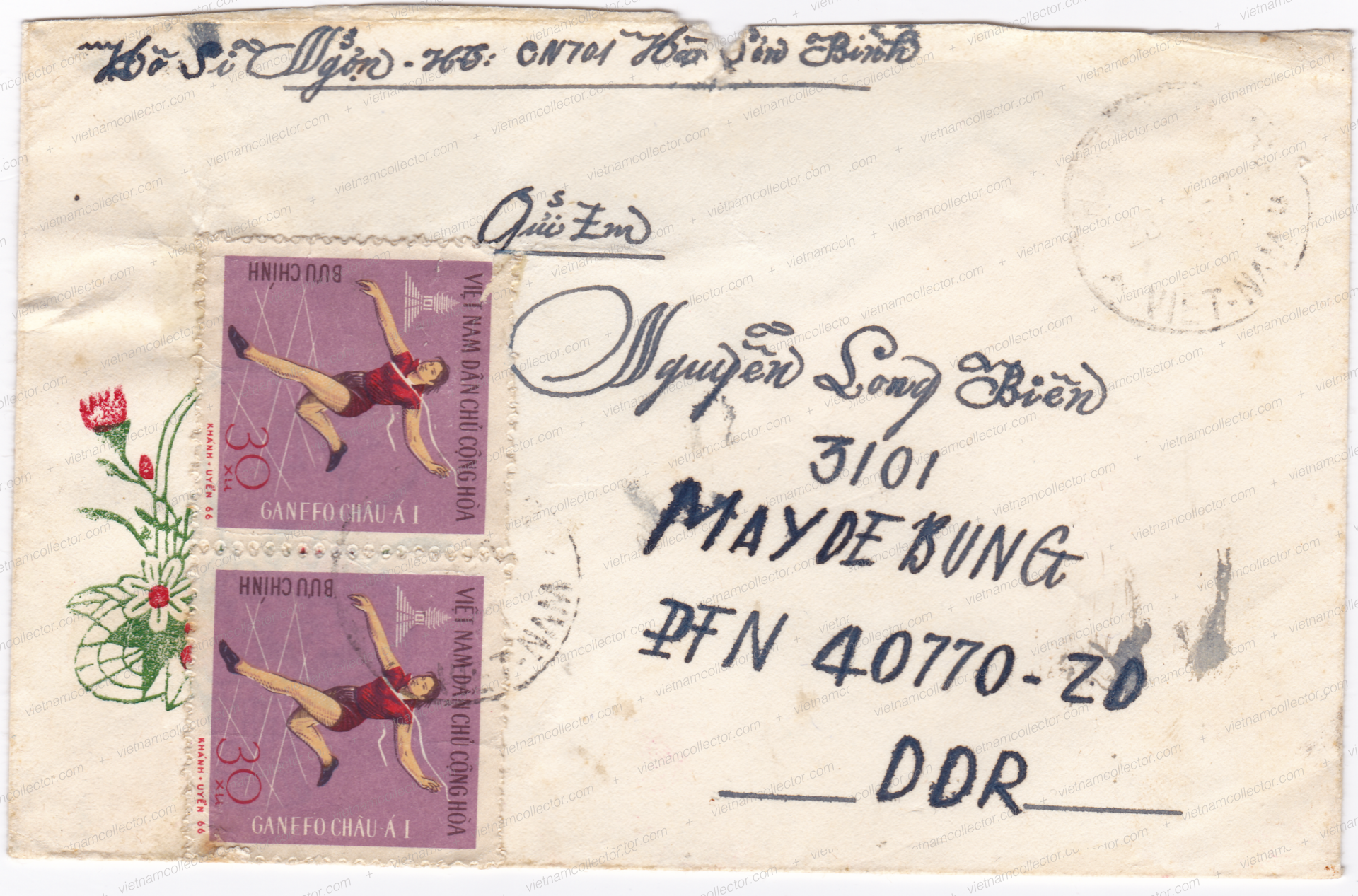

The mail, therefore, became for many the only means of staying in touch with their loved ones. Letters to the guest workers had to include the alphanumeric guest worker number the person was registered under as it served as a virtual post office box. That allowed the correct delivery of mail even in large housing facilities with many inmates, many of which had similar names or names that, for the average German or Czech postman, were just hard to distinguish.

When “The Wall” fell in 1989, East Germany alone had 94,0001 contract workers. Two-thirds of them were Vietnamese1. The newly united German Government went to terminate most of these contracts by paying the respective workers a measly €1,500 in compensation, and sending them home. Some people managed to hang on after applying for political asylum and today they are well integrated into society.

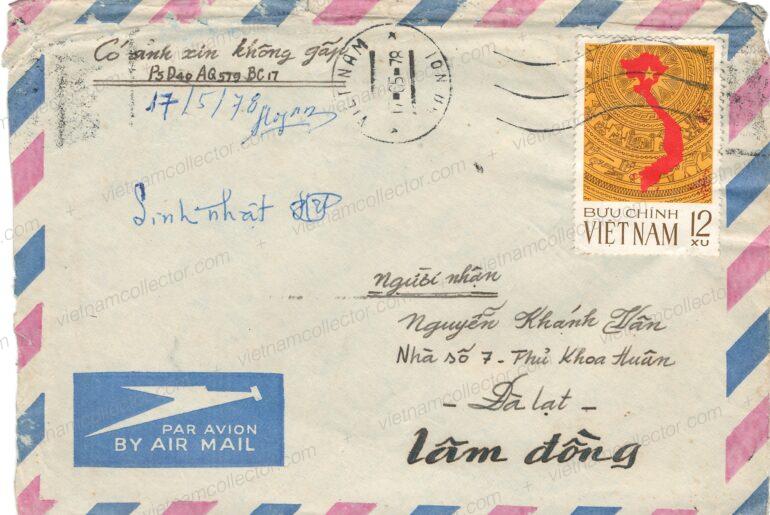

Letters to contract workers are not especially rare but they are part of postal history and, as such, worthwhile preserving. Also, the higher postage required for international letters makes for some interesting frankings. Letters from the early period (1960-1975) of contract workers tend to be pricier, as the international mail volume coming out of North Vietnam during that time was simply so much smaller as the comparable mail that was shipped out of South Vietnam, and there were less contract workers around than in the later period. Also interesting for the collector are military mail postings, often from relatives, which use Vietnamese military free franks. Only one free frank was required for a domestic letter but a minimum of two of the free franks had to be attached for international letters, more if the letter went by air mail or exceeded the first weight level. So, military mail to contract workers is an interesting way to demonstrate a multiple franking of the same stamp issue. Sometimes, one will also find interesting mixed frankings of regular postage stamps and military free franks. That is the case when the person working for the military only had one free frank left and had to upgrade for the international postage by using a regular postage stamp.

So watch out for these alpha numeric codes on Vietnamese letters travelling to Eastern Europe!

[1] Wikipedia

Comments are closed.