Like most countries part of the philatelic world, South Vietnam issued so-called postage due stamps. These stamps were for internal and official use only and they were intended to pay for under- or unpaid day to day postal services. The first such stamps were issued on June 16, 1952, (Michel Suedostasien, 2015) depicting a stylized dragon and inscribed with the words „Timbre Taxe“ (Stamp Tax). This was a full year after the first general postage stamp was issued for South Vietnam. Of course, this begets the question what were post offices doing in the intervening 12 months with letters that were un-franked or under-franked.

Indochinese stamps were frequently used in mixed frankings with South Vietnamese stamps but this practice came mostly to an end on April 1, 1952, when most Indochinese stamps became invalid. This deadline did not apply, however, to Indochinese Postage Due stamps. Post offices still had stocks of the last postage dues stamps issued by Indochina in 1943 or earlier and could use them to charge for any postage that may have been due. Exhibit 1, which was graciously provided by fellow SICP member Ronald Bentley, is such an example. The letter was mailed in June 1951 from India to Vietnam. It was franked with 6 Annas, which was the correct rate for an areogramme from India to other Asian countries after August 15, 1947. (Indian Philatelic Digest www.indianphilately.net/intlairpostalrates19471957.html)

However, the envelope did not represent the lighter areogramme but a regular air mail letter with an inclusion and that cost 10 Annas at the time. The post office in Saigon therefore charged 3.00 Piastre in the form of postage due stamps issued for Indochina in 1931.

Despite the fact that these stamps were for internal post office use only, they were widely disseminated by philatelic services to collectors in both ‚mint’ and ‚cancelled to order condition’ (including FDCs). As such, none of these stamps off cover or on FDC represents a great challenge to the average collector. This, however, changes greatly if one is interested in South Vietnamese postal history. For more than 20 years the author has tried to collect all South Vietnamese postage due stamps on postally used cover but has yet to succeed. By observation of the author less than 25 envelopes carrying South Vietnamese postage dues stamps were offered during that time period on either commercial stamp websites or in dealer auctions.

Contrary to North Vietnam postal history, which is hard to find until about 1975, plenty of South Vietnam postal history, even for the early years, has been preserved for collectors. This would suggest that in this large trove of material there should also be plenty of postage due stamps on cover, but this is just not the case. Of course, one has to wonder as to why this would be the case.

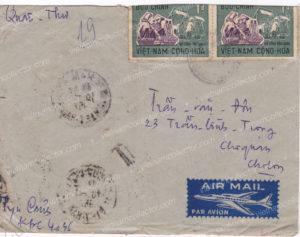

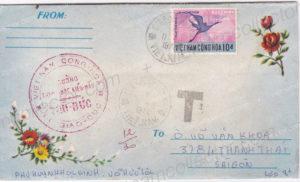

The author is not aware of any South Vietnamese postal regulations accessible today, that describe the use and application of postage due stamps. As such, one depends on the actual surviving envelopes to reconstruct them. Generally, a large „T“ struck mostly in black (rarely in red) was applied to envelopes that were un-franked or under-franked and that were detected in the mail stream. No centrally produced hand stamp was issued for this task by the general postal administration, but it appears that each post office put it upon itself to procure such a hand stamp. As such, the appearance and size of the „T“ varies greatly. Sometimes the „T“ is set in a triangled frame. Exhibit 2 shows an envelope mailed in early November 1967. The envelope weighed just under 5 grams (luckily the content is preserved), so it qualified for the standard 3.50 Dong internal air mail rate in force at that time. (Tarif des Lettres pour le Viet-Nam-Cambodge-Laos-France et Union Francaise 1962)The letter, however, was only franked with a total of 2.00 Dong, which means that 1.50 Dong in postage was missing. This, plus a penalty, was collected in the shape of fifteen 0.20 Dong postage due stamps of the 1952 issue that were affixed to the back of the cover and cancelled with a Saigon-Cholon hand stamp. Also on the back of the cover is a hand-written remark stating „3$“ presumably done by the postal clerk, as a reminder on the amount to be charged. The penalty amounted to 100% of the missing postage as a deterrent to people who may have been tempted to send under-franked letters on purpose in the hope of getting away with it. What is interesting in this context is that the postage due stamps were used 15 years after they were intially issued and despite the fact that updated postage due stamps were published in 1955 and 1956. This clearly suggests that these stamps did not find much use and sat around in post offices for a very long time.

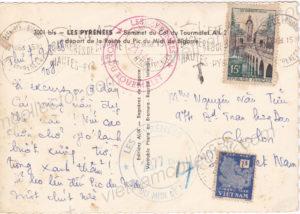

Postage due did not only apply to domestic letters but also to mail received from abroad. Exhibit 3 shows a post card mailed on August 12, 1958 from France to Cholon, Vietnam. The 15 Franc rate apparently was not sufficient hence, the card was hand stamped with a large black „T“ and a postage due stamp of 1.00 Dong of the 1952 issue was added prior to delivery.

Unlike most simplified postal tariffs today, the South Vietnamese postal tariff was kind of complex. Rates for air mail changed for every 5 additional grams that were added to the contents of an envelope. That was not the case for surface mail, that was a bit cheaper than air mail and that was charged in increments of 20 grams, 50 grams and 100 grams of weight. Letters travelling inside Vietnam were slightly lower in rate than letters adressed to locations in Cambodia or Laos. Letters to France or other destinations had yet different tariffs. And so on.

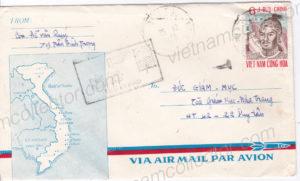

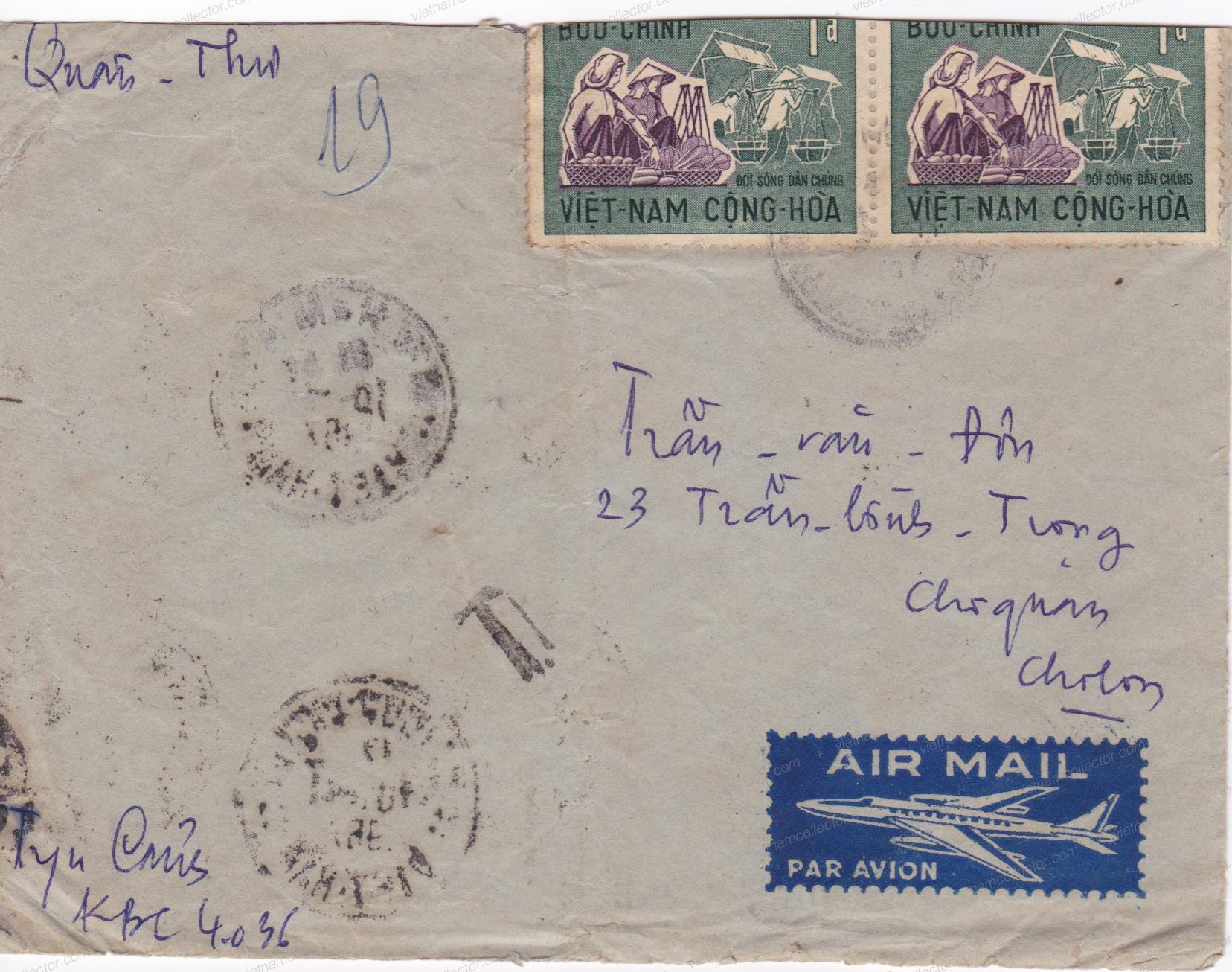

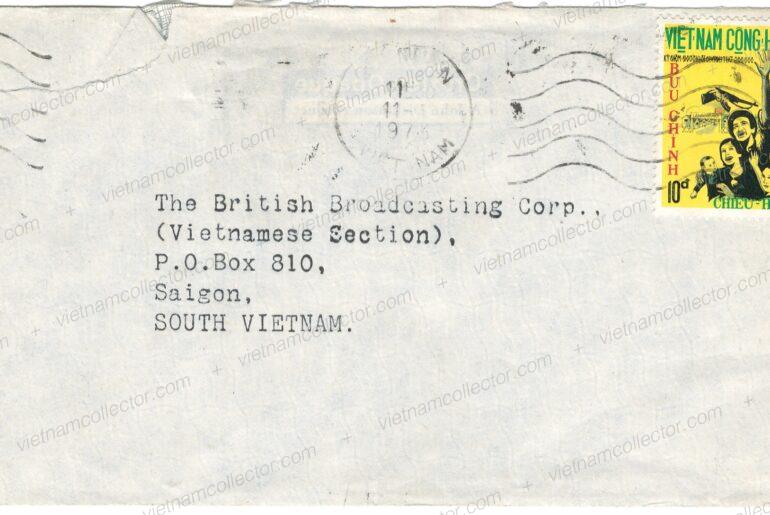

The tariff was certainly confusing to the average postal user, but this did not stop there. Even postal clerks often were not aware as to what the correct rates were in force, especially in the 70s when postal rates were only in force for a few months due to high inflation, or they simply could not be bothered to enforce postal regulations. This is evidenced by the many under-franked letters the author has found over the years that were transported without any marks or penalty. It is pretty clear that the clerk who applied the „T“ on the front of the envelope as a sign of postage due, was not the same person who later levied the penalty. It would make sense that the receiving post office would determine the postage that was due, but that the delivering post office would collect it from the recipient. This division of labor which apparently was not financially reconciled later on, however, created conflict of interest issues. Exhibit 4 shows a letter mailed December 29, 1973. It was franked with only 6.00 Dong, albeit the correct standard letter rate was actually 15.00 Dong as of November 1973. (John Caroll, Domestic Postage Rates of South Vietnam, SICP Journal 153, May 2002)

As such, it was flagged by a black „T“ set next to the stamp. There is no evidence that the missing postage of 9.00 Dong plus 9.00 Dong penalty was ever collected. The author has found plenty of such letters that were initially marked up but lacked any visible follow-through. Now this does not neccessarily mean that the recipient got away „scot-free“. It may just mean that the postage due may have been collected by the mailman in cash, upon delivery of the letter and without receipt. After all, people wanted their mail, and what were they to do if the mailman demanded extra postage before handing over the item? Countries with poorly paid civil servants were and are fertile grounds for corruption and it makes sense that the post man would supplement his meager income with the occasional cash collected for un-paid or under-paid mail, especially if there was no ledger in the receiving post office on what penalties were to be collected. Now, this is of course, just a theory but when one considers the general lack of use of postage due stamps, it certainly resonates. SICP member Lucian Lu has also suggested that the penalty often times was simply not collected.

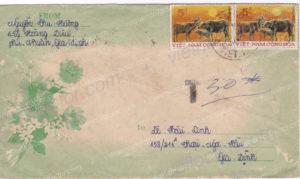

Exhibit 5 shows a local letter that was mailed on July 17, 1974 with two 5.00 Dong stamps affixed to the front. In April of 1974, the standard letter rate had increased to 25.00 Dong (John Caroll, Domestic Postage Rates of South Vietnam, SICP Journal 153, May 2002); so the letter was 15.00 Dong under-paid. A large black „T“ and the handwritten number „30“ were added and the Gia Dinh post office levied 30.00 postage due (15.00 Dong postage plus 15.00 Dong penalty) in the shape of the three 10.00 Dong postage due stamps issued in 1955 depicting a large dragon. Again, these stamps were still in stock at the post office almost 20 years after they had first been issued, and despite the fact that new versions of postage due stamps were published in 1956,1968 and 1974. This is further evidence that these type of stamps were not used very often and it supports the theory that penalties were more commonly collected in cash without any receipt.

In 1956, additional postage due stamps were issued depicting a fire breathing dragon. The nominal value of these stamps was rather large (stamps in 20.00 Dong, 30.00 Dong, 50.00 Dong and 100.00 Dong were published), which begets the question what was their intended use? After all, the domestic standard letter rate was only 1.50 Dong until January 1957; so it is not very likely that these stamps would have been useful in surcharging the average under-franked domestic or international letter at that time. Rather, it is more likely that the high values were used on heavier mail (keep in mind that packages up to 3.00 kg could be mailed as „letters“) which wrappers were mostly discarded after opening. As a result, virtually none of these high value stamps affixed to a parcel wrapper or other large commercial mail seems to have survived. The author could only find so far one letter that carried a 30.00 Dong stamp of the 1956 issue. It is shown in Exhibit 6 and it was mailed on September 11, 1974, carrying a single 10.00 Dong stamp in front, flagged by a large, black „T“. At that time, the standard letter rate was already 25.00 Dong. (John Caroll, Domestic Postage Rates of South Vietnam, SICP Journal 153, May 2002) The 15.00 Dong shortage and the 15.00 Dong penalty was paid using said 30.00 Dong stamp, 18 years after the stamp had first been issued!

SICP member Lucian Lu indicated that these stamps also had a fiscal purpose that exceeded postal use. In the 1970s the South Vietnamese Customs Authority created custom inspection offices in large post offices. Their intent was to investigate the content of the many packages that were incoming from abroad. Many imported items were subject to duty at the time and when the inspector located an item on which duty was due he/she added the amount of duty payable in the form of cancelled postage due stamps on the custom documents. While the author does not collect revenue stamps, he has never seen such a custom document with SVN postage due stamps on E-Bay or Delcampe. May be the customs documents were simply for internal use and were not handed out to customers. The author would be grateful if any of the revenue stamp collectors of the SICP could weigh in with their expertise.

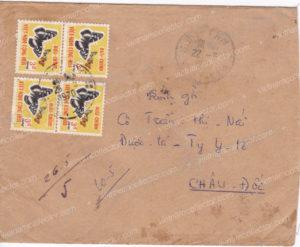

The 1968 issue, depicting butterflies, showed nominals between 0.50 Dong and 10.00 Dong that made sense for standard letters given the tariff in force at the time. As a result they are a bit easier to find than the older stamps issued in the 1950’s but by no means are they common! Exhibt 7 shows an unusual letter mailed on May 20, 1970. This is unusual in the sense that this is the only piece of mail that was mailed without any pre-paid postage the author could locate, so far. All the other letters at least pre-paid some of the postage. The standard letter rate until February 1972 was 6.00 Dong (John Caroll, Domestic Postage Rates of South Vietnam, SICP Journal 153, May 2002), so the postage due stamps of 12.00 Dong covered the missing postage (6.00 Dong) plus the penalty (6.00 Dong).

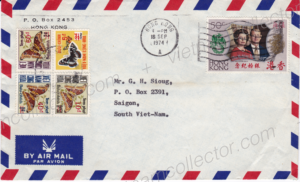

On October 1, 1974 (Michel Suedostasien, 2015), the postal administration surcharged some of the postage of the „Butterfly Stamps“. This had become necessary as large inflation in the late 60’s and early 70’s increased postal rates quite dramatically. Between August 1969 and April 1974, less than five years, the domestic letter rate increased by over 700% from 3.00 Dong to 25.00 Dong. These surcharged stamps could have been used for only a fairly short time period. Saigon and with that the Republic of South Vietnam, fell on April 30, 1975, which only left seven months in which these stamps could have been used. Genuine letters with these stamps are extremely rare. So fare the editor has only seen one genuine cover carrying some of these stamps. So beware of forgeries! Below is a letter that was sent from Hong Kong to Saigon in September of 1974 and the 115 Dong worth of overprinted postage due stamps were added. Unfortunate the letter is a partial forgery. While the cover from Hong Kong to Vietnam is without question genuine, the postage due stamps were added at a later time by someone to defraud philatelists. This is based by an assessment of the Vice President of the Hong Kong Philatelic Study Society Ingo Nessel. The first class postage rate for a 1/2 Ounce letter from Hong Kong to Vietnam was in fact just 50C. Since the correct postage was paid there was no requirement to charge for any postage due. Had the letter been heavier than 1/2 Ounce the Hong Kong Post Office would have added a remark on the cover to alert the Vietnamese Post that the letter was under-paid. There were established regulations and markings to that effect in Hong Kong at that time. Clearly, Vietnamese postal clerks did not possess the knowledge of over 165 postal tariffs around the world to make a judgement if a letter was in fact under-paid. They always required the sending country to provide this information. Also, letters that were judged by the Vietnamese Post as under-paid received a black hand stamp “TT” in larger post offices or a manuscript “TT” in smaller ones to indicate to the delivering clerk that additional postage had to be collected. None of these markings are present on this cover. While the Vietnamese cancel on the letter is illegible beware of very similar covers that feature Vietnamese postage due stamps that carry a Saigon-Cholon canceler. The editor was offered a cover very similar to the one below that also carried a 50C Hong Kong postage, no postage due remarks and two of the overprinted stamps (5D and 10D). This cover was canceled by the Saigon-Chalon cancel with a date from February of 1975. So, clearly, someone is manufacturing these covers using a misappropriated or stolen South Vietnamese cancel. Many of these cancels were lost or stolen after the Fall of Saigon and are now obviously used to produce forgeries.

Registration No. 400900

Comments are closed.